On a 2014 episode of the beloved Canadian-American kid’s show “Arthur,” everyone is getting into this really weird band—except for Binky. Known among his classmates for having refined musical taste and talent, Binky decides to listen to the band only after another character, Muffy, teasingly suggests that “it might be too sophisticated” for him. “Too sophisticated for me?” he boasts incredulously. “I know music better than any of you!” He takes the headphones from the show’s eponymous aardvark—who, hearing the band, felt like he was “on another planet”—and Binky presses play.

A flurry of brooding strings begins to modulate, bassy percussion rumbles in periodic crescendos, followed by an explosion of dissonant horns. The piece contradicts itself, evoking radically different emotions; yet they oddly manage to correlate with each other. Is this even children’s music?

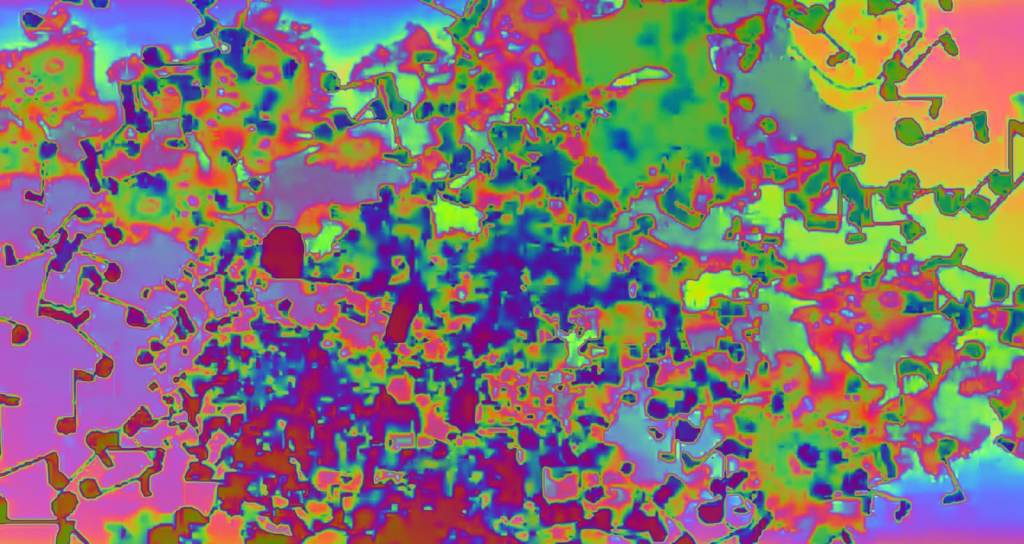

After falling into a reverie, where he’s swirling over trippy fractals and transcribed notes flying in random directions, Binky can’t stand it anymore and throws off the headphones. “What on earth was that!” he exclaims while trying to catch his breath. It was “Big Beautiful Dark and Scary,” composed by Julia Wolfe and performed by the Bang on a Can All-Stars. They’re the house band for Bang on a Can, the multi-purpose contemporary classical organization (summer festival, commissioning fund, record label, and more), based in New York and founded by Wolfe along with the composers David Lang and Michael Gordon. Although they’re widely known in new music, BoaC are certainly unfamiliar to the average television audience. Yet their appearance on “Arthur” made an unpredictably large wave.

You’d think that classical music and popular internet memes are sectors totally separate from each other. But soon after “Binky’s Music Madness” aired on PBS Kids, the home channel of “Arthur” in North America since 1996, the reverie sequence of Binky listening to Wolfe’s composition became precisely that: a popular internet meme. According to the online encyclopedia Know Your Meme, it’s referred to as “Binky Listens To” and is one of numerous “Arthur”-related memes to gain traction in the past few years. In one video, “Big Beautiful” is replaced with a song by rapper XXXTentacion, and this has been viewed over 1.9 million times on YouTube. Some of the first popular videos involve artists associated with the forum-site 4chan.org, specifically their music board called /mu/: Binky is seen listening to the noise-rap group Death Grips in a 2014 clip and the “vaporwave” producer Macintosh Plus in 2015. (4chan users have hailed these two experimental-leaning artists and helped catalyze their success beyond the realm of /mu/, mainly by creating memes out of them.) The most recent video to garner a major view-count—over 300,000 within the past two months—is themed around the anime Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure.

Creating memes about composers and sheet music is certainly a phenomenon, except they’re propagated within a niche online audience. While “Binky Listens To” may not be a classical music meme in the same sense, its very basis—which has been invariably overlooked by the internet’s mainstream, even as new Binky videos continue to get uploaded—is preeminent contemporary classical.

David Steven Cohen, the writer on “Binky’s Music Madness” among other “Arthur” episodes, recounted a recent conversation with Julia Wolfe (who was unable to be reached for this article). “I saw her at a Bang on a Can Marathon in May and the first thing she said was, ‘Have you seen the memes?’” he told me. “Wherever she goes, [fans] talk to her now about them. Sometimes, they even show the memes when she’s giving a talk or making some sort of appearance. We didn’t discuss the particular music used in the memes, but Julia embraces so many styles, genres, and cultures as a composer, I’m sure she’d be engaged by all of it. She’s certainly tickled by how much attention the memes have gotten.”

A veteran television writer, Cohen has been a passionate fan of BoaC for years, and when the head writer asked if he’d be interested in writing an episode about avant-garde music, he suggested the All-Stars. Hence the anthropomorphic musicians, including Julia Wolfe as an actual wolf. “Their music spans so many different styles, and they’re really wild and provocative—so emotionally expressive,” he said. “Their artistry is sublime and their humanity infuses their music.” He later found out about the resultant meme through one of his sons. “When my son Gabe was telling me about the meme, he said, ‘Did you know [BoaC] did Brian Eno’s “Music for Airports” live?’ I was impressed to hear any of those words coming out of my son’s mouth. But I guess I wasn’t surprised.”

“Arthur” is the second longest running animated show in North America, and like the show in first place, “The Simpsons,” its writers have taken some liberties in terms of who they want to have as guest stars. It made sense for “Arthur” to center an hour-long special from 2002 around the Backstreet Boys, who had released an 8x platinum album two years earlier. They’ve devoted episodes to much lesser known artists like the All-Stars—or baritone Rod Gilfry, the focus of an opera-themed episode from 2004. “The Simpsons” is canonical enough to get away with featuring animated cameos from, say, Sonic Youth or Thomas Pynchon without having its ratings seriously affected; and the same applies to “Arthur.”

However, the All-Stars’ presence isn’t a mere affectation for “Binky’s Music Madness,” because the group actually functions as a meaningful plot device. Following his experience with “Big Beautiful,” Binky hears everything around him as music: a faucet dripping in his kitchen, branches tapping against his bedroom window at night. A Cageian ideology is encroaching and he can’t escape it, no matter how much he tries to practice Beethoven and take refuge in traditional classical music. He creates a short musique concrète piece out of the everyday noises that have been aggravating him, then plays it for his classmates to mock what he interprets as their shared belief that anything can be considered music. They dig the piece, and making it wasn’t even an easy process—Binky suddenly realizes that it took him three whole days.

The All-Stars, standing in the classroom doorway, are into it as well, and the episode ends with the musicians and kids all jamming out to Binky’s musique concrète with live instruments. This encounter ties into the group’s multimedia project “Field Recordings,” where composers, including Wolfe, wrote music to pre-recorded material: “bridging the gap between the seen and the unseen, the present and the absent, the past and the future,” according to Wolfe’s website. In distilling the philosophy behind “Field Recordings,” BoaC challenged musical expectations for kids who watch “Arthur,” ultimately teaching a lesson in open-mindedness.

“Found sounds [are] an ideal way to broaden a child’s concept of what music can be or [what music] is, so it was a perfect melding of the avant-garde with something a kid might get,” Cohen said about drawing inspiration from “Field Recordings.” “One of the things I try to do in writing for children is make them more artistically and creatively aware of the world around them.”

Contrary to what might’ve seemed a probable byproduct of going viral, it doesn’t look like the All-Stars have amassed a brand new fanbase of meme zealots. After all, the punchline has been Binky’s reaction to the piece—transpiring amid the memorably outrageous sequence of trippy fractals—rather than the piece itself; the All-Stars’ role has been anonymized. But the “Arthur” writer is happy with how the internet has responded, and all the different kinds of music that’ve been used in place of “Big Beautiful.” According to what he told me, Julia Wolfe is equally verklempt. “It’s wonderful,” he says. “You write an episode and five years later, it’s like a playlist of weirdness that comes back to you, based on a moment in that episode. You just never know.” ¶