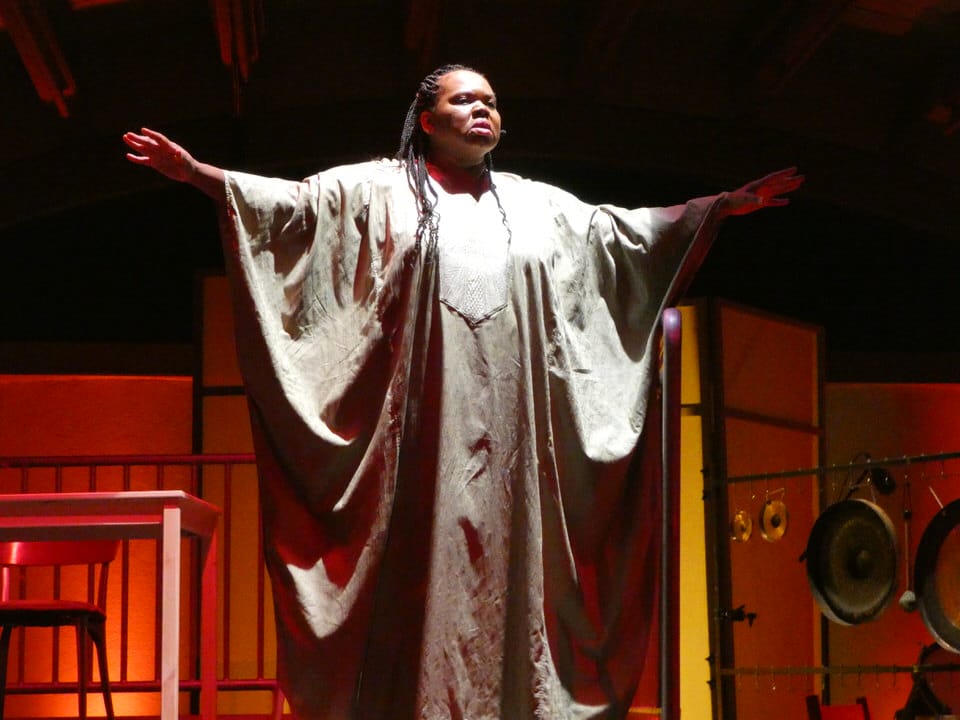

During this year’s Ojai Music Festival in Ojai, California (June 8-11), I met up with George Lewis, the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University, to discuss his opera “Afterword,” which received its West Coast premiere at the festival on June 9. The theme of this year’s Ojai Music Festival, directed by Vijay Iyer, was community and empathy, and special attention was given to the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a collective of African-American musicians founded on the South Side of Chicago in 1965. Many of the festival’s featured artists and composers had either participated in or been influenced by the AACM, which—as a collective of musicians transcending genre boundaries—served as a model for the type of community envisioned by Iyer. Premiered in 2015 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, “Afterword” is a two-act chamber opera composed by Lewis to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the AACM. He also wrote the libretto, based on the final chapter of his 2008 book A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, in which he depicts a fictional meeting between AACM members living and deceased who are reunited to discuss the organization’s history and hopes for the future. Drawing on recordings of past meetings and interviews that Lewis conducted, the opera presents this meeting as a series of episodes in which the same three singers serve as avatars of the organization’s thoughts and beliefs.

VAN: The theme of this year’s Ojai Music Festival is community and empathy. Each of the festival’s concerts presents its own interpretation of this theme. How is this theme addressed in your opera “Afterword”?

George Lewis: Community is essential to the opera’s themes. What we’re seeing is a community in formation. People are coming together to find commonalities, and they need to come together because nobody is really supporting them.

The idea of African Americans defining themselves as creative musicians [went] against every known grain at the time. Very important kinds of music that we now recognize were routinely denigrated in the press. Jazz… not creative at all. African-Americans… no history, no creativity, suppressed, denied, expelled, censored. So in that environment an association makes perfect sense. It might not make the same kind of sense if you’re from a community that is being regularly supported. Then individual strategies might make more sense because in fact the community is already there and is already favoring you.

In this case, what we’re seeing is community formation, all throughout the opera. And we’re seeing the stresses and strains of community formation—disagreements of different kinds. But at the same time there is a need to forge a community that is accepting of different points of view. This is when you get to the empathy part. Empathy is also fundamental to the creation of this community; we need empathy to establish community. People need to be receptive and open. They need to even make themselves a little vulnerable, and we see this in the opera as well. There is a sense in which people aren’t sure what’s going to happen.

Generally in the AACM, after it got going, anyone’s ideas were considered great. No one ever told you your ideas were not good. People like Muhal [Richard Abrams]—their idea was basically you already knew the truth about your work. You just needed to face it and deal with it. And it wasn’t like you needed to stop anything. You just needed to be aware.

Awareness is another part of empathy and community. Not least the awareness that you are in a community. You’re not just an individual, a lone individual trying to gain advantage. You realize that your advantage comes when everyone is lifted together and you work together.

I’m going to add a third aspect of community, which I will call service. You need to serve. The AACM was there not just to serve the musicians’ careers. They started a school. They were serving other people. You got there at 8:00 a.m. You prepared the classroom, and then the students came in—some of them were kids, some were adults—and you taught them theory and how to play musical instruments. You were serving the community. The students weren’t paying anything. They probably couldn’t afford it. And those were my best lessons in composition. I try to maintain that kind of sensibility of empathy and community in my teaching as well. But certainly in the opera, it’s there all the way through.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

One of the ideas that really fascinates me about your AACM book is the concept of genre mobility. My understanding is that it’s a way of resisting how certain people—critics, record companies, audiences, and other musicians—label your music.

Not everyone has mobility of genre. As I pointed out in my book on the AACM, mobility of genre is often gender- and/or race-dependent. At least in the United States, genres have often been racialized. We knew which ones were black or white, and that was the most important aspect of genre. Classical; that was white. Jazz; that was black. Or, sound art; that’s still white.

When you look at genre this way, it becomes a racialized resource, which is differentially available for use and support. As genre scholars say, genres support intelligibility. Alright, but the issue is that some people who think they understand you because of your genre—they don’t see that the genre is shot through with racialization, which actually makes you unintelligible.

In other words, there is a point at which some people can draw on a genre and others can’t. That means that genre is an infrastructural component. When you look at genre in terms of infrastructure, you see that certain genres have more access to infrastructure than others. In the past, jazz musicians didn’t have access to the support and funding available to the so-called composer—which was assumed to be a white category. If you were a composer, it was assumed that you need these kinds of infrastructure and can benefit from them and benefit society, culture, and history. And if you were a jazz musician, [it was assumed that] you didn’t need support—you could just “go up there and do your thing”—and funding wasn’t important.

That may seem a little harsh, but let’s get to the mobility part. The mobility of genre is the mobility of people, not the mobility of the genre. The genres aren’t so mobile. I wrote about John Zorn, for example. John, who has been my friend for many years, can pick and choose. He’s used to that. He can be classical one day, jazz the next; he can be noise music. These are all different aspects of his personality… and his musical catholicity and the vast knowledge he has about music, which is enviable and the result of hard work and love.

I noticed when I was writing my book that the AACM was manifesting a similar mobility, but not given any credit for it. People kept coming up with the same genre markers for [the AACM musicians]. The classic example [was] the “former jazz musician,” which was a category reserved for whites. There is a standard trope in classical music of the former jazz musician—like Mel Powell, Harold Budd, maybe Bob Ashley, and Donald Martino. They had a youthful moment in their lives when they were jazz musicians, and then they were able to get out of that and into something else.

But could Anthony Braxton be a former jazz musician? Whatever jazz is, which is so ill-defined, it seems that anyone could be a former jazz musician. But the answer to my question was clearly no. Whatever he did, that same marker came back to him. And that marker was culturally disfavored in terms of access to infrastructure, which is how you get support. Certain genres make it more difficult for you to access infrastructure, which is more than just funding. Infrastructure is also critical sensibility—the way your music is written about and studied, and how it’s presented in academic institutions and the media.

Certain genres are invested in and others are disinvested in. You wind up seeing what you can try to do with that. With regard to the post-genre strategy, you can say that for yourself, but quite a bit of the time, genre is imposed upon you from the outside. Genre is communitarian, but it’s not necessarily empathetic.

You refer to “Afterword” as a chamber opera. Did you have any models for the piece? Did you try to push the genre boundaries of the chamber opera?

There have been a lot of chamber operas lately. Brian Ferneyhough’s “Shadowtime” is a chamber opera and is, in several ways, a model for what I do.

If opera is a genre or practice, “Shadowtime” pushes the boundaries by having neither a linear storyline nor narrative development of the characters. But I’m not so sure how much narrative character development there is in opera anyhow—as opposed to a novel, for example. Ferneyhough was working in a didactic sort of way. For instance, Adorno is set to music. You’ve got Charles Bernstein’s language poetry, which is about the power and meaning of words and sounds.

And so a lot of linearity is smashed in Ferneyhough’s opera. By not having a story, “Shadowtime” received a very bad review in The Times. But it inspired me. I went to see the opera and thought it was great. I was looking for something like that. Instead of depicting the life of Walter Benjamin, it depicts his ideas. “Shadowtime” is an opera of ideas. My opera could be considered an opera of ideas, but it’s more a community opera, where sociality is brought to the fore as a means of creating community.

Let’s talk about the other thing, pushing the genre boundaries. Anthony Davis pushes genre boundaries in the way I’m doing—and he did it long before me—through introducing new subjects. A big change in historical periodization—according to Fredric Jameson, for example—is that you’ve got all kinds of new people there who were previously considered non-persons, but are now considered subjects. Most of these new subjects are people of color and communities of color, and they can be from regions such as Africa and parts of Asia. Certainly they’re on the table as forces that have to be dealt with, and their humanity has to be taken into account by the majoritarian narrative in a way that isn’t exoticized. They can’t be easily dismissed. They can’t be caricatured. They have to be taken as fully-fledged subjects and have to be viewed on that basis.

Anthony Davis does that with his opera about Malcolm X (“X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X”). That’s an incredible subject for an opera. There’s everything you need: a hero, tragedy, and triumph. But when Davis wanted to write an opera about Malcolm X, he had to face pretty strong opposition. I don’t know if anyone’s ever written about this, but one of the signal meetings around the production was the meeting between Beverly Sills and Betty Shabazz. In spite of their differences, they came together to create a new community that would support the idea of an opera about Malcolm X. Somebody had to say that maybe opera can go beyond valorizing people who are already being valorized by society.

It’s these new subjectivities that push the boundaries. Regarding the musical boundaries of opera, I don’t think there are any really. You can do pretty much anything. You have so many different ways of approaching opera. The first step is the sound. I do, however, see boundaries in terms of the subjects being depicted. It’s the question of who gets depicted as a subject—that’s the boundary-pushing project.

For “Afterword,” you collaborated with the singers Joelle Lamarre, Gwendolyn Brown, and Julian Terrell Otis. It seemed to me like your vocal writing was tailor-made for them. Could you describe your process of composing for the singers?

My working process was a little bit more hermetically sealed, because I was just writing music. We [also Sean Griffin and Catherine Sullivan, co-directors and developers of the 2015 Chicago production] had to do the things that you normally do at operatic auditions. We were looking for people who could act but also really sing and learn very difficult music.

I didn’t know the singers that well. What shaped my vocal writing more was a concept of prosody. I’ve heard a lot of contemporary music in which the composers take the prosodic aspect of the poetry and basically shoot it dead. They introduce all kinds of things like melisma or stretching out syllables, making the text unintelligible. That was an avant-garde technique for a while. I didn’t want to do that. And I took a lot of heat for that from some quarters. Some people thought that my opera was not avant-garde enough. But I thought it was an old strategy that wasn’t going to be helpful.

My idea was that the AACM book was written so that younger generations of the AACM would know what they had been a part of and what had been achieved by the organization. With the opera, I really wanted it to be something where people could listen to it without the supertitles. That meant eliminating things like melisma. My vocal writing was very syllabic, and it was dealing with the natural rhythms of a certain line. I wanted it to be almost like speaking when it’s singing, but not be sprechstimme. My goal was to have the text be understood by everybody.

Related to that, I thought the music was there to support the text. The music really only comes out during the costume changes. Even though the rhythms and sounds are quite forbidding, I was still trying to be accessible in terms of the text. I’m not making that into a style, and I might change that in the future. With this opera, because there is an educational aspect to it, I wanted people to understand the words. ¶

Updated 6/23/2017.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.