In his essay “The Paradoxical Theory of Change,” Gestalt psychiatrist Arnold Beisser wrote that “change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not.… It does take place if one takes the time and effort to be what he is.”

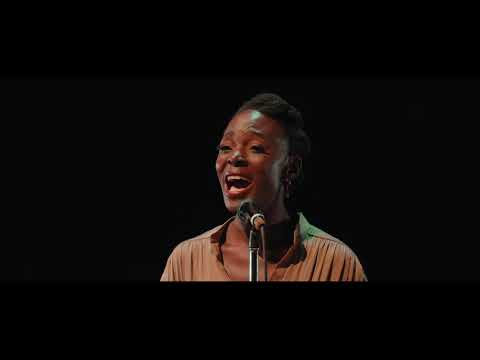

I quote this line a lot, but it felt especially resonant while speaking with flutist and composer Nathalie Joachim. Joachim was 10 when she began her studies at Juilliard as part of its Music Advancement Program. In 2005, she became the first person to graduate from all three of Juilliard’s main programs: the MAP, Pre-College, and College divisions. Despite this—or perhaps precisely because of it—Joachim’s career has diverged broadly and frequently from what the expectations were for a Juilliard graduate in the early 2000s. Instead of seeking an orchestral position, Joachim has combined conservatory-honed technique with a roving curiosity to forge a path as a composer and flutist, one who also works voice and electronics into many of her works, both as a solo artist and as one-half of the art-pop duo Flutronix (along with fellow multihyphenate Allison Loggins-Hull).

Beisser argues that it takes effort to be what one is. Joachim (who still teaches at Juilliard) concurs: “That’s always been a part of my personality, wanting to achieve or to be doing all of the things that I’m supposed to be doing.” Her efforts have paid off, most recently with the Grammy-nominated “Fanm d’Ayiti” (2018), a work for which Joachim conducted hours of sound recordings and interviews including with her grandmother, in her family’s home village of Dantan, and the country’s underrepresented female vocal artists. The musical dimensions added in by Joachim, at once precise and expansive, add dimension to her collected oral histories.

We spoke about her love of archives, writing for Pamela Z, and music-making with her grandmother. But first, and in the spirit of history, I asked about her connection to a long-shuttered record store that once sat next door to Lincoln Center.

VAN: In a few previous interviews, you’ve mentioned that the Tower Records at Lincoln Center was formative for you as a musician.

Nathalie Joachim: I very much miss that place. A lot of growing and learning happened there. It was such a fixture in my life that coincided with my classical training in a very specific way.

What way was that?

I started the Juilliard prep programs when I was 10. Because I was so little, my mom was like, “You can go to Barnes & Noble, you can go to Tower Records, and you can go to Ollie’s. Anywhere else, you have to check with me first.” And so I used to just run over there during my breaks.

Now we have Spotify with, Here, this is what you should listen to. But [then] it was amazing; there was this incredible crew of invisible angels who would curate these listening stations for you. You could listen to whole records and really discover. I totally did that and, as a result, I was exposed to a lot of music that I would not have ever… I hate when people say, “Oh, I have such an eclectic musical taste.” But I think that it did allow me to really open my ears to what the possibilities of sound could be.

You’ve mentioned working with research a lot in your music. Are you working on something specific right now that’s research-based?

Flutronix has a big project that we’ve been working on for years called “Discourse,” which is really community-centered. The Southern Oral History Program was a huge partner: They have an archive of over 6,000 oral histories of people who were born and raised in the American South, and we accessed a lot of those archives, especially in the beginning with neither of us really having a rich connection to or understanding of the region. Allison’s family migrated as part of the Great Migration; her grandparents were one connection back to Mississippi, and they very rarely talked about their life before Chicago. So it was a nice way to begin to be connected with that space as two people who don’t really have a rich understanding of the history there, and the archivists there were exceptionally helpful.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

When you’re working on this sort of project—and “Fanm d’Ayiti” seems to fit in this category as well—it sounds like the text comes first. How do you then bring the music in?

A lot of people ask me that question, and I will say that working on “Fanm d’Ayiti” really shifted my practice. Up to that point, I always went into something—both as a composer and a performer—really having an idea of what my hopeful outcome was. That was the first time that I had a really significantly long research phase in which I wasn’t writing music at all. But the nature of the research was strengthening my ability as a deep listener.

In collecting oral history, there was a long time where there just wasn’t any music happening at all. It was the moment when I recorded the girls’ choir in the church that it kind of clicked, like, all of these things I’ve been listening to over and over and over, from the stories to the music to conversations with my own family—I think I understand how all these things are supposed to shift into mutual space with one another.

It also helped me release myself from what I thought the project needed to be, to just allowing it to be what it was. So much of it was really allowing for the material to let me know how it might nestle up against something else, instead of forcing some form upon it. The music does come much later, after a lot of listening. That was true for “Discourse,” for sure. And I’m just finishing up a piece that’ll premiere later this season for the St. Louis Symphony and their IN UNISON Chorus, which is a 120-voice choir that is a collective of smaller Black church choirs from throughout the city. I wanted it to be an opportunity for the chorus to tell the story of the chorus. The oldest member of the choir, who recently passed away but who I did get to interview and feature in the work, was 92 years old; the youngest member of the choir is 20, maybe 21 now.

I started the project right around when George Floyd was killed and we were all… I just wanted to talk to them about what the choir meant to them, but obviously we were all locked inside, there was a pandemic, a lot of wild things happening, and so I got to have these really rich conversations with people who I would have never had a chance to engage with. And the more you listen to not only what they say, but also what is in between what they’ve said—what’s held in the silences of what they said, and how each of their statements begin to connect with one another—that helped shape the piece for me, and it became very clear what needed to come forward in the musical setting and what needed to sit back. What needed space and what could support something else.

You have a number of performances of “Fanm d’Ayiti” coming up this season. First of all, I hope your family is okay? [Dantan was approximately 55 miles from the epicenter of the 7.2-magnitude earthquake that hit Haiti on August 14—Ed.]

Yes, they are.

Glad to hear. The earthquake was just the latest development of a protracted crisis in Haiti. Has any or all of that changed your relationship to “Fanm d’Ayiti” as you prepare to perform it this season?

It definitely makes me much more committed to the work. I think the thing that I come away with is: The more that happens in Haiti, the more I realize that it’s not a place I’m ever gonna leave behind, so it feels good to be carrying it forward with me. Not just through “Fanm d’Ayiti”: My next record is mostly bilingual, Creole and English, and also a deep examination of heritage in self and ancestry in lots of different ways. I don’t know if it’s shifted anything, I think it’s just reinforced what was already there.

There’s so much more than what we see advertised as Haiti. It’s a hard place to stop loving, you know what I mean? Our music is part of so much, because it is how we have carried forward our history for so many generations. Our language really wasn’t formalized as a written language until the 1970s, so even my parents grew up not reading or writing a language that they spoke fluently. So much of our language and our story has been carried forward in our music, and so much of it is rooted in how we have connected with each other for all of time.

You’ve mentioned a few upcoming performances and commissions this season; one thing you haven’t mentioned yet but I’m very curious about is your LA Phil concert in January with Pamela Z.

She is somebody who I have followed probably since I was like 13 or so. She just was this beacon of light, like, this magical Black woman who is working in electronics and very much making her own sound?! Seeing her be herself was the thing; that very thing that I needed to know was possible: doing your own thing, making your own way in a scene where nobody else was really doing that. It allowed me to see a future for myself that was not there in my brain previous to knowing about her.

We’ve been able to develop a friendship since then, but when I was approached by LA Phil to curate a Green Umbrella series, they said, “You could also bring on a co-curator,” and I said, [without missing a beat] “Pamela Z!” So it ended up becoming this dream project: writing for her combines all of my favorite things.

In what way?

My favorite thing about writing for voices specifically is that they’re like a fingerprint. No two voices are the same. Other instruments, it’s like, “Yeah, the flute can do this, and some people can do it better than others, and that’s just how it goes.” Not that there’s no room for discovery or individuality in that. But it’s not quite the same. And there’s this idea of Pamela not only as a vocalist, but, in terms of electronic music, she is one person who I really believe has crafted a language that’s unique to her. It’s almost as if she’s built her own instrument that doesn’t exist elsewhere. So in writing for her, it does feel like writing for this super-instrument that can’t be recreated by anyone else. But I sort of don’t care. [Laughs.] I love the way her mind works. I love that she’s very thoughtful; that she finds a lot of beauty in a lot of the smallest things. There’s something very pure about a lot of her music.

You mentioned just now discovering Pamela Z at the right time, when you were 13 and sort of in need of someone to show you at that point that you could do your own thing. At the same time, you were completing all three major programs at Juilliard. That feels like a major juxtaposition.

I started writing music and engaging in music with my grandmother, centered around Haitian music, centered around telling each other stories through music. That was very free. There were no rules, except you gotta be yourself and you got to be expressive, and you have to be honest in how you’re sharing.… When I first went to the music advancement program [at Juilliard], it was amazing. It was the first time I was like, oh my God, I love music so much, and all of these other nerd kids also love music so much! But it also very quickly taught me to compartmentalize, especially as you go up in those programs.… Everything I was doing at Tower Records was top secret. Everything that I was doing with my grandmother, I was not telling anybody about that. The fact that I listened to top 40 radio was not something I was talking about. It was just very clear that there was this separation.

When I got to college, I knew immediately that I didn’t want to be an orchestral flutist. That grew to be a problem; [at the time] there was also this shifting of generations. The way that all of our teachers and mentors had garnered careers was not the way almost any of us were going to garner careers.… I did have to come into a place of letting go of what I was supposed to be, and supposed to be doing. Nobody could even really tell me [what that was], except that they were like, “Just get this orchestral position!” And I was like, nobody’s gonna get those! No shade, but I don’t even want one of those. So what do I do if I don’t? There must be an answer for what else is there to do. Going to Juilliard instilled this need and desire to be what I was supposed to be, which was so much a classical thing of, You’re supposed to play it this way and you’re supposed to look like this. I just finally, very recently, was like, what if this is what I’m supposed to be? And what if that’s just fine? What if this is just another way, and nobody told me that before because they couldn’t see it themselves, either?

Really, who knows at 11 or 20 or even 25 what they’re supposed to be? I’m in my late 30s and I have no idea what I’m supposed to be.

For sure. I don’t regret [going to Juilliard]. I still have a deep relationship with the school, and I wouldn’t change any of it, it’s so much of who I am. But the life that I’m living now did not occur to me, which is why seeing somebody like Pamela Z when I did was such an anomaly. She was not doing what she was supposed to be doing, but I loved it. It’s why I go back to the time with my grandmother so much. She was the first person—and for a very long time, the only person—who was like, “You are exactly who you’re supposed to be already.” That changed my life. She was really trying very hard to instill that in me from the very beginning. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.