Daniel Grossmann is the conductor and music director of the Jakobsplatz Orchestra in Munich, which focuses on Jewish music. In this playlist, he tells us the brief story of his relationship with the frequently underestimated—particularly in his home country—genre of klezmer.

I hate klezmer. Or do I?

Right now, it seems to me, Germany is obsessed with klezmer music. There are too many festivals, musicians, and bands to count playing the genre right now.

What do I mean when I say I hate klezmer? This judgment is not without inner contradiction for a music director of a Jewish orchestra. But is what has become known as the klezmer style genuine klezmer? The answer is: not exactly. Many years ago, I happened to find out that I didn’t hate klezmer. What I recognized back then was that I hadn’t actually known what klezmer was.

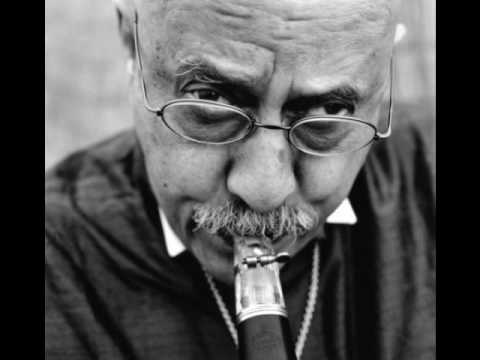

What we call klezmer today goes back to the wonderful work of the clarinet player, Giora Feidman. Here is a typical example called “Freilach,” meaning “merry” in Yiddish.

I’m reluctant to say that I can’t understand why this kind of music is so popular. I don’t mean Giora Feidman’s virtuosity, which I do find fascinating. But for me, this music lacks in variation; it all sounds uniform in a way. I zone out after a while and stop paying close attention.

It happened once though that a Muslim friend from a Turkish family showed me a klezmer recording at a party. I was taken aback: is this real klezmer?

Yes, it was. And suddenly I understood what my problem had been. Klezmer hails from the Eastern European shtetl, it used to be festive music accompanying weddings and other celebrations. The music per se wasn’t called klezmer; klezmorim were the musicians that played this Yiddish, mainly instrumental music.

Jews left the shtetls as a result of repeated pogroms. Most of them moved to the U.S. This meant, more or less, that the original tradition of the klezmorim and their music came to an end. Now they had to make a living in their new homeland, they had to adjust to its cultural environment—and so did their music. They called it klezmer but it was different from what they had played back in their shtetls.

This development can be very well illustrated with the example of a legendary clarinet player, Naftule Brandwein. He was born in 1889 in a Galician shtetl into a family with 13 children, emigrated in 1908 to the U.S. and became known under the stage name “Nifty” as the “King of Jewish music.” According to a legend, he turned his back to the public while playing so that he could keep the particularities of his technique a secret. This recording makes clear how much he was influenced by the American music.

The recordings my Turkish friend showed me at the party, however, were rare specimens from the beginning of the 20th century. They documented the still-unadulterated art of the shtetl musicians. The contemporary klezmer is related to this music only within certain limits. I discovered a world of much rougher and richer sound behind the hissing and rushing of the recordings’ poor acoustic quality. In place of a clarinet’s krekhts (wailing) accompanied by a guitar and a double bass, there were entire orchestras playing with astonishingly skill and sophistication.

After I started to explore the origins of this music I quickly found out that the wedding ensembles in shtetls consisted, depending on the financial means of the newlyweds’ families, of 10 and up to 40 musicians. I learned also that the clarinet wasn’t the only lead instrument; other leads could include the violin, dulcimer (zimbl), trombone, trumpet, and many more. In view of the current terminology (which goes back mainly to the klezmer-renaissance of the 1970s in the U.S.), this recording could hardly be characterized as klezmer.

And in the following piece of the Belf’s Romanian Orchestra, entitled “Amerikenskaya,” the historical development of klezmer is translated backwards into music: here we no longer have the American musicians enacting shtetls. Instead, the shtetl orchestra enacts America.

And that’s how I found myself infatuated with klezmer. ¶