Veteran opera manager Anthony Freud has led the Welsh National Opera, the Houston Grand Opera, and most recently the Lyric Opera of Chicago. This summer, he is retiring and returning to his home in London. On a Zoom call, we looked back at his long, varied career in opera. Freud spoke with practiced eloquence about the challenges of fundraising, his favorite singers, and what opera houses across the Atlantic can learn from each other.

VAN: On April 7, you watched “Aida” from the front row—the final performance of your 13-year tenure as general director of the Lyric Opera of Chicago. What did that feel like?

Anthony Freud: This is probably not the answer you were expecting or wanting, but actually what I was focusing on was the “Aida” performance, and my responsibility for making sure it was as good as it possibly could be. I have to say, after all these years being responsible for opera companies, I’m no more relaxed at performances than I was 30 years ago. Maybe less relaxed. I was in the front row because at Lyric, those seats are traditionally the general director’s seats, and it felt right that as it was the closing night of “Aida,” I should at least sit there for that too. When the performance ended, that was when perhaps my thoughts went more in the direction of reflection. And it feels a bit strange, I have to say.

Which opera productions do you want to see as an audience member next season?

Since I moved to the U.S., which is now 18 years ago, my summers have been spent at various European opera festivals on a rather regular basis. So actually, what I’m looking forward to when I move to London is enjoying the extraordinary theater and concert scene [there].

Which opera house would you have liked to manage if fate hadn’t brought you to Chicago?

Chicago was my dream job. I’ve been very lucky in my life. I have to say, if you’d asked me when I was a very young teenager what I wanted to do when I grew up, I would have said, “I want to run an opera company,” and here I am. In retrospect, I can’t imagine three more contrasting and complementary companies to be responsible for than Welsh National Opera, Houston Grand Opera, and Lyric Opera of Chicago.

I’ve always said that I don’t believe in the idea of a generic opera company serving a generic city. I believe that every company has its own personality, focus, and strategic priorities. What I’ve tried to do is really understand the personalities and potential of each of those three companies. As someone who grew up in London, as someone who, until 2006—when I moved to Houston—had only had a European perspective professionally, the idea of moving to a city as un-European and as 21st century as Houston, Texas, and trying to understand how this 400-year-old art form with European roots could be relevant to that city and could actually become an indispensable part of that city’s cultural landscape, was something that I derived incredible excitement from. And then moving from Houston to Chicago, having begun to understand the nature of life in the non-profit performing arts in the U.S., understanding the differences between Houston and Chicago and the differences between Houston Grand Opera and Lyric has been incredibly stimulating and challenging.

How would you describe the difference between the American and the European approach to opera?

I do think there is little depth of understanding on both sides of the Atlantic about life in the arts on the other side of the Atlantic. I think the simplistic stereotype of my European colleagues assuming that American general directors are kicked around mercilessly by unconscionable wealthy donors is as wrong as the American perspective of European general directors dreaming about art and waiting for the next public funding check to drop through the letterbox.

I very much enjoyed the American system. The U.S. is a single market, a single system, based on the assumption of no public funding of any significance. [There is] a reliance upon a combination of earned revenue through ticket sales and contributed revenue through contributions, a system that makes it cost-efficient for those lucky enough to be wealthy to be generous in their philanthropic giving. I obviously spend a lot of my time in the U.S. fundraising. I happen to enjoy it very much. I happen to really like interacting with donors and prospective donors because it’s a wonderful, engaging way of getting to know somebody.

But nobody should think that my life as general director of Welsh National Opera was any less involved in fundraising. It’s just that the people with whom I was interacting about fundraising were very different. They may be politicians, civil servants, or representatives of one of the two arts councils that were funding Welsh National Opera: Arts Council England and Arts Council Wales. I suppose the big difference in the fundraising experience is that in Britain I was rarely able to interact with the individuals who themselves could make funding decisions.

The European system is less direct.

Yeah. In the U.S., I’m lucky enough to be interacting with the people who themselves can make the difference directly on a very regular basis .

And just for the record, throughout my nearly 20 years in the U.S., I have not once encountered a donor who has been anything less than extraordinarily responsible, conscientious, and self-aware about their role as a philanthropist, just to dispel the European stereotypical perspective. It could not be more wrong, in my opinion.

Would you argue that private funding gives opera houses more artistic freedom and flexibility?

It’s impossible to generalize, but in my years in the U.S. I’ve definitely never felt that the system undermined or diluted artistic freedom. Over the years, it’s now become even easier to fund more unusual contemporary work in opera, for example. I think the circumstances differ from country to country and from opera house to opera house. In Germany, for example, there is an unparalleled depth of political and public commitment to culture that extends to cities, to regions, to the federal government. That has resulted in an arts infrastructure in Germany that is frankly the envy of the world.

In the UK—and I speak at a time when I think arts funding in the UK is under particular stress—since World War II and the establishment of the principle of public support for the arts through arm’s-length agencies called arts councils, there is a network of highly accomplished, world-class opera companies that can only function because of public funding, but that have levels of public funding that are insufficient to allow [them] to operate at the right level. And so life in the UK in the arts can be very schizophrenic, because you have to both deliver what your public paymasters are expecting and also position yourself to be able to attract private funders, and obviously build productive relationships with those private funders. It’s a complex issue and it’s a subject that I wish was more deeply understood on both sides of the Atlantic.

Is there anything else that opera companies on both sides of the Atlantic could learn from each other?

I believe very strongly that we exist for our audiences and therefore the relationship between an opera company and its audiences, its stakeholders, has to be a very dynamic one. I suppose that relationship is intensified when a company is fully reliant upon the financial support of its stakeholders. A company that is more reliant upon public funding than on income generated by those who want to support it creates a different dynamic in the relationship between an opera company and its audience.

Matthew Epstein, a former artistic director with Lyric, recently told the New York Times, “The problem is the ability to raise funds the way [former Lyric general director] Ardis Krainik did is done.” Has it become harder to raise money for opera?

It’s always hard to raise money for opera. You have to understand the donor that you’re dealing with, and find a way of aligning our strategies and priorities with those of the prospective donor. The world has changed. The city has changed. The company has changed. People’s expectations, tastes, and interests have changed. What we can never afford to do, if we hope to succeed, is think of ourselves in some sort of bubble, existing independently from the world around us. I agree with what Matthew Epstein said, but I don’t complain about those differences. I celebrate those differences.

Before you started as an arts administrator, you pursued a law degree and qualified as a barrister. Has that background helped you during your career in opera?

Every day. I’ve never stopped being grateful for my legal training. You’re trained to analyze, to think, to present an argument on both sides of an issue. I think it’s self-evident how in a job like mine, with its really extraordinary mix of objective and subjective issues, that legal training is incredibly valuable.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Maybe one of the reasons that some people have reservations against opera as an art form is that pop music celebrates the untrained voice: pop singers whisper softly into microphones, and avoid wide vibrato or pitches at the extremes of their range. How would you go about convincing someone of the beauty of a big operatic voice?

I would say, “Let me invite you to an opera performance. You don’t have to read up about it in advance. You just sit down and have an open mind, open eyes and open ears, and the bug will bite you just as it bit me as a young teenager in London in the early ‘70s.” I think part of the point of opera is the transformational power of the live experience, which is visceral. It’s not intellectual. It’s almost impossible to define: You just have to come and feel it for yourself. If the opera performance that you’re seeing is good enough, I believe it will work its spell. But I do believe that it has to be good enough. Because in my mind, while there’s nothing as great as great opera, there are not many things as bad as bad opera. And I care about the quality of what I’m responsible for—mainly for the sake of someone coming to the artform for the first time—because if it’s good enough, it will work.

And yes, what is regarded as mainstream entertainment at the moment is very different from the entertainment value of opera. But my instinct is to celebrate those differences, to bring someone into an opera house and let them know that what they are experiencing is completely non-electronic. It’s the unamplified sound of 150 people making music theater together. And yes, a great operatic voice sounds different from a great exponent of popular music. But celebrate that difference and enjoy both. One is not more worthwhile than the other.

Nevertheless, audience numbers, at least here in Germany, seem to be in decline.

Our experience at Lyric is that audience numbers are not in decline. This season we have grown our audience by 15 percent. Between last season and the one before, we’ve grown our audiences by more than 20 percent. I think it’s very important for the sake of the artform to focus on growing audiences both in size and in diversity. I do think the range of stories that you tell is incredibly important, and that’s why when we present a new or recent work, we intentionally pick works that are about things that resonate with people living in Chicago in 2024. And that may be different from what resonates with someone in Berlin in 2020.

At the same time, I also believe very strongly in the value and the power of what you might call the heritage works—so long as you present them through a contemporary lens. These great works need to be interrogated. There is a reason why these works transcend the centuries, but it’s our job as a producing company, in the way we present and interpret these works, to generate an awareness of their relevance, to generate discourse around some of the issues that they raise, and to actually persuade audiences not simply to be passive observers, but to be actively engaged participants in a great classic work.

How do you do that?

In the way you interpret them and introduce them to audiences. When I started going to the opera 50 years ago, it was normal to present the title character of “Don Giovanni” as a suave, charming, seductive aristocrat. But really he’s a rapist and a murderer. And I do believe that it’s our job never to shy away from the issues and the subtexts of the works that we are guardians of. We need to alert people to their complications, complexities, and subtexts. We have to take a view about those pieces and not shy away from interrogating them. These are strong, tough pieces that have withstood the test of time. They can certainly withstand the interrogation of anyone choosing to produce them today.

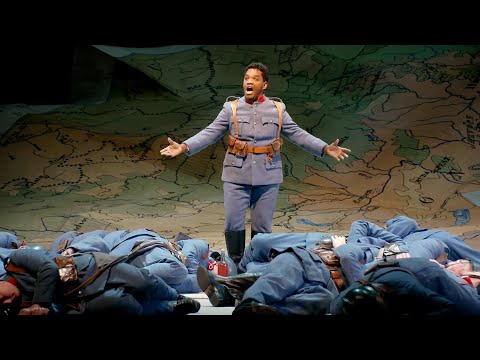

“Champion” by Terence Blanchard is a good example of an opera that resonates with a modern, local audience. Did the numbers show that that piece brought in new audiences who wouldn’t necessarily go and see a “Don Giovanni”?

I believe it did. What has been encouraging this season is that around 27, 28 percent of our audience for “Champion” was new to Lyric. But what was equally encouraging was that the same percentage of new people came to “Cenerentola,” which was done at the same time as “Champion” over the course of this season. [According to the Lyric press department, 24 percent of the “Champion” audience was new to the house, while 22 percent of “Cenerentola” listeners were new.—Ed.”] It’s a statistic that I’m still startled by: 27 percent of our audience was new. And to be honest, that belies your question in terms of the assumptions about opera audiences declining and dying.

According to the New York Times, the number of subscribers at Lyric Opera of Chicago has gone down.

It’s true that if you go back 20 years our entire season was sold out on subscription, and that was a badge of pride for Lyric at the time. At the same time, I celebrate the fact that our seasons are not sold out on subscription, because if they are, you can’t grow your audiences. You can’t attract new people into the opera house. We still really value our subscribers. It’s something like [47] percent of our audience that is made up of subscribers, which is still an incredibly important proportion. But that allows us to actually develop new audiences and to introduce people to the art form and to Lyric.

Who is your favorite singer?

When I started going to the opera, I had a number of favorite singers of that era who absolutely entranced me and who cemented my addiction to opera. I suppose three who were very present in different ways in my early opera-going days were Joan Sutherland, Jon Vickers, and Leontyne Price. I had the good fortune to experience them live many times. Vickers and Sutherland were regular artists appearing at Covent Garden through the ‘70s and ‘80s. So I went often to every performance, not just every opera that they did.

Is there a quality that they have in common?

Extraordinary individuality. The artistry of Joan Sutherland and the artistry of Jon Vickers could not be more different, but each of them was completely unmistakable, and each of them presented something that was the opposite of generic. Experiencing Sutherland in the opera house was an amazing experience that transcended pure singing. Even though she wasn’t in a conventional sense a great theater actor. Nevertheless, her performances in opera houses were extraordinarily theatrical, but it was theatricality on her own terms that was built from this amazing sound that she made.

And one of the really life-changing experiences that set me on my path to being an opera missionary was going to a Proms performance of “Peter Grimes” in 1975. I got there really early, and as soon as the doors opened, I ran down the stairs into the arena and I got my spot on the rail. What I didn’t know, because I couldn’t have planned for it, is that I was on the rail directly in front of Vickers. Vickers was no more than two or three meters away from me, and there was nothing and no one between me and him. The sheer visceral punch to the solar plexus of experiencing Vickers singing Peter Grimes has never left me. I came out of that concert thinking, “If this is what opera can do to me, I want to persuade as many people as I possibly can to experience what I’ve just experienced.”

Do you think that the trend toward contemporary opera in the U.S. will continue?

America is incredibly fertile ground for new work and has been for some time. If you think of the creation of “Dead Man Walking,” for example, in 2000, and the number of new works that have been created in the first 24 years of the 21st century—it’s an astonishing number. The very fact that so many companies around the U.S. are commissioning new work on such a regular basis, and so many companies are producing recently commissioned work that they haven’t created themselves, but that they give extended life to—that should make us very optimistic about the future of the artform in the U.S.

What was the most challenging moment during your time as a general director?

COVID. My most challenging moment was at 2:30 on Friday, March 13, 2020. We were two weeks away from opening a new production of “Götterdämmerung” and about four weeks away from the first of three complete “Ring” cycles. Happily we had already given performances of “Das Rheingold” and “Siegfried” in the three years leading up to that moment. But a “Ring” is the most ambitious undertaking any opera company can contemplate; it’s a ten-year process, and until maybe three days earlier, I still thought, “Somehow we’ll deliver it. Somehow it’s all going to work out fine.” And then very quickly, it became very clear that cancellation was the only option. And assembling the whole of the company on stage and saying, “We now, as of this moment, have to cancel the ‘Ring’ because of the pandemic”: Nothing comes close to that in terms of professional trauma. And of course, it got a lot worse because we then had to cancel the entire following season.

Did the original production of the “Götterdammerung” ever see the main stage?

Not yet. It exists. It’s been rehearsed, but not performed. Planning a “Ring” has felt irresponsibly ambitious, given the uncertainties of the current climate. I believe that Lyric and the “Ring” will meet again. And so hopefully this production of “Götterdämmerung” and this production of the whole “Ring” will find a life at Lyric at some point in the future. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.