By now, the figure of Julius Eastman needs little introduction—though this was not always the case. Active as a performer and composer in many corners of the eclectic, sometimes contentiously fragmented landscape of late 20th-century American music, Eastman carved a singular path, adjacent to many worlds yet beholden to none. His music can shock as much as it can transfix. Its moments of raw power are juxtaposed with trance-inducing tranquility; its searing pain is countered with luminous, unbridled joy. This music, like its creator, resists firm categorization. It is all-embracing and uninhibited, unapologetically so.

The story of Eastman’s life is equally complex. Trained at Curtis, Eastman collaborated with many of the era’s major musical figures, performed on the world’s great stages, and was a key member of the Creative Associates at the University of Buffalo, then a nexus of the American avant-garde. Still, by the 1980s, he struggled to find steady work as a teacher and performer. An eviction from his East Village apartment led to the loss of many of his scores. He died in 1990 with little fanfare, having lost contact with those in his social and professional circles.

In recent years, however, a renewed interest in Eastman’s work has blossomed. Led by people like composer and scholar Mary Jane Leach, who set out to collect and reconstruct the scores and recordings that had been lost upon his death, and scholars Ellie Hisama and Rénee Levine Packer, who collected oral histories from his colleagues and family, Eastman’s music has experienced a posthumous renaissance. His Second Symphony, his only surviving work for orchestra, was brilliantly recorded by Dalia Stasevksa and the BBC Symphony Orchestra; an ongoing recording series by the LA-based collective Wild Up is poised to offer definitive recordings of his complete chamber works.

I first encountered Eastman’s music as a student when I played “Stay On It” with my school’s new music ensemble. A few years later, while working on a performance of “Femenine” with the BlackBox Ensemble, I was introduced to Isaac Jean-François. Now a PhD candidate in African American and American Studies at Yale, Jean-François has become a leading scholar and thinker on Eastman’s life and work.

Over the last year, Jean-François and I have worked together to curate a project, “Speculative Listening: The Sonic World of Julius Eastman,” that asks: What if we aimed not just to listen to Eastman, but with Eastman? What might such an approach reveal about the person and the music? (The resulting program will be presented next month as part of Bang on a Can’s Long Play Festival, with a subsequent performance at the Whitney Museum.)

Last weekend, we met on Zoom to recount some of the recurring themes of our year-long exploration of the composer’s work. We discussed Jean-François’ initial encounters with Eastman, the focus on the body in his research and how it can change the way we listen, and the implications of doing so on our contemporary understanding and reception of this singular figure.

Excavating Eastman

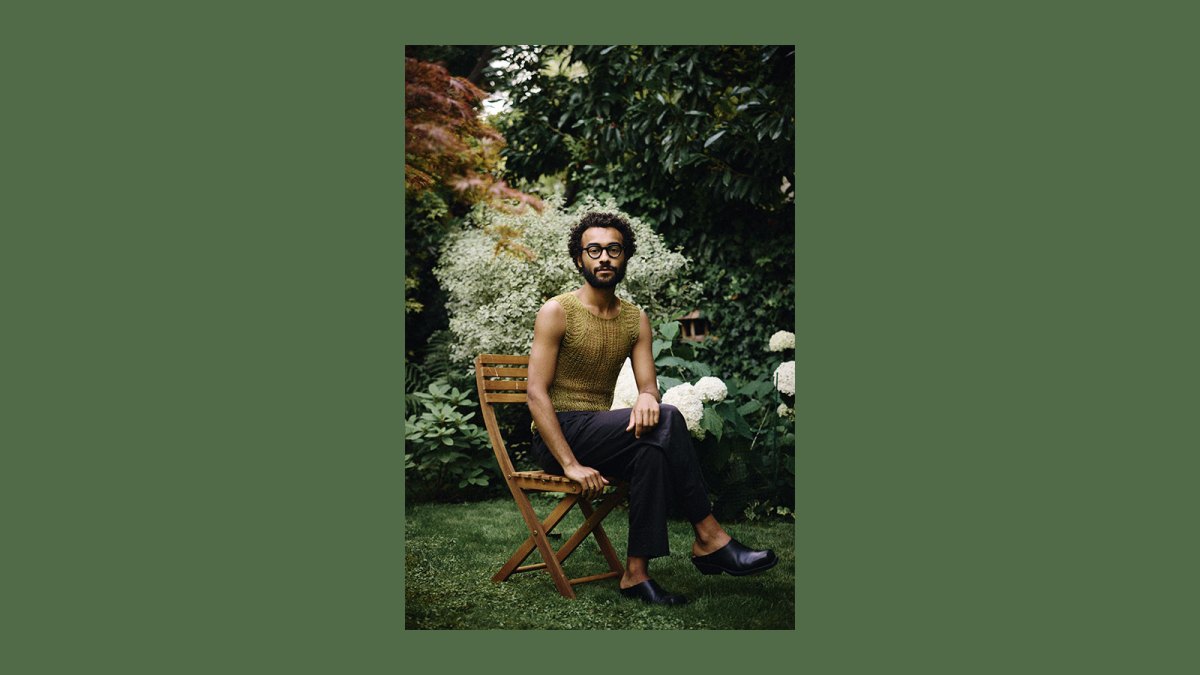

Musicologist Isaac Jean-François’s encounters with an elusive artist