In his long career, Riccardo Muti, 81, has led top orchestras and run major opera houses; for a brief moment about a decade ago, there were rumors he would become Italy’s ceremonial head of state. Muti’s fierce stare is imposing and inspirational—he’s an Italian conductor out of central casting, but with better hair than Arturo Toscanini or Victor de Sabata. The Lisztian black mane now has a little gray in it after 55 years of conducting (he first became a music director in Florence at the age of 26), but Muti remains a dramatic presence both at the podium and in person, though he leavens his gravitas with humor. Muti relishes telling jokes, employing expert timing and punctuating them with huge smiles and laughter. In English, he also employs a Seinfeldian use of ellipsis—instead of “yadda yadda yadda,” Muti uses a shorthand for “etcetera, etcetera, etcetera” that sounds like “chettera, chettera.”

For an artist so associated with Italy, Muti has spent a great deal of time in the United States—he’s one of only a handful of conductors to lead two of America’s “Big Five” orchestras—yet for all his symphonic appearances, his operatic output in the U.S. is limited to a mere seven performances of “Attila” at the Metropolitan Opera. But opera remains a key component of Muti’s musical mastery, which he gave audiences a taste of during his “farewell tour” of the U.S. this spring with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the ensemble he’s led since 2010.

Muti spoke with me about his tenure in Chicago and his long career on both sides of the Atlantic backstage at a new concert hall in Orlando, Florida during a day of rehearsals. That evening, he lead a performance of Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition,” which he will also play with the CSO at Carnegie Hall’s Opening Night Gala this October.

VAN: What’s the difference between conducting in a big city and touring with an orchestra in the U.S.?

Riccardo Muti: Even when I was with the Philadelphia Orchestra [from 1980 to 1992], I always found it very interesting to tour the United States. I’m used to these big halls: the Philharmonie [in Berlin], the Musikverein [in Vienna]; but in the smaller cities you have a public that is even more with you during the performance—there is a gratitude, not for the conductor, but that “you came to us.” And this is a part of America, the American public, that should be known more in the world.

In my life, thanks to Philadelphia and Chicago, I’ve been to Wichita, Des Moines, Ames, Toledo… For me, to make music, it’s not that I conduct in Salzburg and I try my best. Because every time you try your best, it’s a disaster. Everything becomes mannered, exaggerated, chettera, chettera.

And sometimes you don’t want to conduct a concert, and so you are in a sort of passive mood, and the concert is not only good—it’s better. So, for me, it’s not important “where”: the big city, the big hall, the historical hall. I’ve done all that enough. But when I come to these places, I find the real people. That’s the reason that I like very much to travel in America.

In Europe, it’s different. When you go to smaller cities like Karlsruhe or Wuppertal, there is always a sort of sophisticated audience, and because their city is smaller or less important than Vienna, they want to show they know more. That’s not the case here. They just appreciate us coming.

In America, you primarily conduct in concert halls, whereas in Europe you’re also well-known as an opera conductor. The programs on this “farewell” tour are mostly symphonic—but the encore is from an opera. Why?

Opera is very important. Why is the Vienna Philharmonic so special? Because they play symphonic music every day. And then they also play opera every day. When an orchestra plays opera, it naturally must sing.

The encore, the intermezzo from “Fedora,” has a great melody. But the piece is a somewhat light, dare we say trivial, opera. You made Giordano sound almost Wagnerian—and I noticed that it was the only piece in the rehearsal where you stood up.

Italian opera should always sound that way. Italian opera is good music and “Fedora” is good music—Giordano was from where I am from, in the south of Italy, and he is too often dismissed, which is the fault of lazy singers and conductors. It is always very important to me that these composers, especially Verdi, can be heard as they should be heard.

You have long had the reputation of being a strict, no-nonsense conductor of Verdi. In the past you were known as an authority figure or a stern disciplinarian. But watching you conduct here and in Chicago, you seem to be having fun?

Maybe at that time, I wanted to make a point about Verdi. And also, I was younger. So, I [had] the attitude of the Italian Maestro, the Toscanini school… But it was not an attitude that was scientifically planned. It was just my feeling at that time, a reaction to things I was hearing. And here I don’t have to prove anything anymore. As Otello says in the opera, “Ecco la fine del mio cammin”—it’s the end of my voyage. I’ve done all I want, not only with the orchestra, but with myself.

So, with these musicians I am like a father or an older brother. Except for the principal trombone, Jay Friedman. He’s legendary, he was hired by Fritz Reiner.

The Chicago Brass is such a signature strength of the CSO. What is it about them that makes them so special?

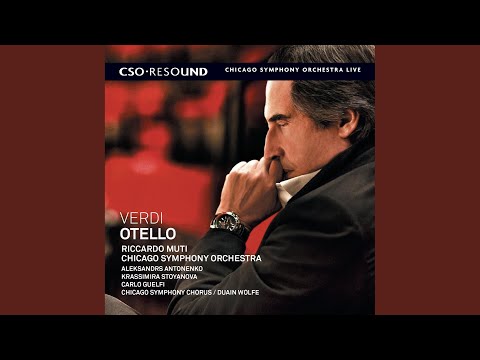

I think that I have actually changed the relationship—changed the balance—between brass, woodwinds, and strings here. Before, when I was in Europe, I was tired of hearing all about “the Chicago Brass this, the Chicago Brass that.” OK, [they are] exceptional, sure. But what about the rest? In a way, something was not right, because the woodwinds were good but not great, except some—some—individuals. The strings were a little bit harsh. Just a little. Now, they sing. And that was especially thanks to the Italian operas we’ve done, “Otello,” “Aida”…

I think that the orchestra’s more balanced now. When I need the brass to play like they do in [Tchaikovsky’s] “Manfred” Symphony, they can still do it. But now, it’s more balanced throughout the orchestra: much better strings, very beautiful, and an exceptional group of woodwinds. The woodwind chorales, when they play like an organ together, are really exceptional.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

You’ve been guest conducting in Vienna for over 50 years, but you haven’t been back to Philadelphia for almost 20 years. All this time in Chicago, you’ve been only 750 miles away. Why haven’t you gone back to Philadelphia?

I will go next year [for] the Verdi Requiem.

So there’s no bad blood? When you left it seemed sudden, a surprise?

No, I haven’t been back—not because of anything, but because I am very loyal to the orchestra here. [He motions next door, where the CSO is rehearsing on stage.] When I was in Philadelphia, I only conducted Philadelphia in America. So now in Chicago, only with Chicago. If I have one more week free, why should I give it to anyone else?

The last time you conducted the Verdi Requiem in the States was in New York, in 2002. The New York Philharmonic let you hand pick an all-star cast of opera singers, they really wanted you as music director. Why didn’t you want to lead the New York Philharmonic?

Of course I did. I loved the New York Philharmonic, and they loved me. And I still love them, and I have great memories of the concerts we did together. But after almost 20 years at La Scala and with all the troubles… Even with 20 years of a great relationship—but then, you know, politics in Italy, it is… well, we all know.

And so, I said, “That’s it. Basta. I want to be free. I was able to keep this theater in my hands for 20 years, but now, I want to be free, to be back in Vienna, Berlin, [conduct the] Bayerischer Rundfunk, the Orchestre National [de France]…

But… But… [He takes a deep breath.] I was almost at the point to sign.

Really? With New York?

Yes, Zarin Mehta came to Paris with a contract. I was not sure whether to take this responsibility. You know, to be a real music director—it’s not like today. Today, a music director is a principal guest conductor, he just conducts more concerts, that’s all. But a real music director has to take care, and not only musically. The musicians must feel free to knock on your door and say, “Maestro, we have this problem.” It’s not only musical. That is a music director. If not, what is your profession? Just to say, “It’s sharp. It’s flat. It’s sharp. Obbligato”? That’s nothing. Today, it’s changing. The world is changing. And now conductors have two orchestras and a theater? Three theaters and an orchestra? That is… Well, let’s not say that it’s immoral. But certainly, it is not artistic. In this way, I am of the old school.

Can one be a music director of the old school in America today? Or in Europe? Anywhere?

The Generalmusikdirektor in Germany or Austria, but Germany especially, has more power. In America, you have the board of directors. The president. The chairman. The vice-president. The this. The that. Chettera, chettera. In Toscanini’s time, you had Toscanini! He used to say, “A real music director is somebody that opens the door with his key in the morning, and in the evening closes the door with his key.” But that is in the past.

After Chicago, would you take on another music director title?

No, but before I conduct in Philadelphia, I’m going to Sarajevo—that is important.

Why Sarajevo?

For many years, I’ve done the Roads of Friendship concerts every year. The first time was many years ago in Sarajevo. We landed with the La Scala orchestra in a military plane; the normal plane couldn’t land since the city was bombed. The first thing that they needed was music. The war was really cruel. And they arranged this stadium cover so 9,000 people could attend, and I invited the musicians of Sarajevo to join the La Scala musicians. We gave them the instruments because so many had been lost in the bombing. In the second week in October, I will go back to Sarajevo. The orchestra in Sarajevo will celebrate 100 years of existence. So, for this big celebration, I will go and conduct the concert.

This is important to me. At my age, I don’t have to have success. Even when I was younger, for me music was… to say it is a mission is too arrogant. [He puffs his chest:] “A mission.” No, I am not a missionary. But I really believe, and I’ve fought in my country for decades against governments or anyone [else who] stops music from being played. The importance of music is not because music is some sort of rhetorical phrase; it is the music.

Music is important because it doesn’t have words. So, it cannot have political messages. But it can be used for political purposes. For example, during the Nazi period, the Beethoven Fifth Symphony. Instead of being played in the Beethoven style: “Dum-Dum-Dum, Dom…” It became: “Dum…… Dum…… Dum……… Dom…” to impress the people [with their power]. It was used wrongly. Then poor Bruckner, who was a religious man: his music was used as a sort of political tool. But music generally has no political message, but rather a spiritual message.

Can conducting become more inspirational and less dictatorial?

I hope so, but I will probably not see it, because as I said earlier, like Otello, “this is the end of my voyage.” I may not see it, but one day I think that the relationship between public and conductor and orchestra will—and must—change. We dress like penguins, and then we go out and we play. That inter-relationship before the concert, a sort of involvement, the performers with the public, explaining—but not like a professor… The performance must be something much more human. A concert is not just me, one way. No, a concert is “we are together.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.