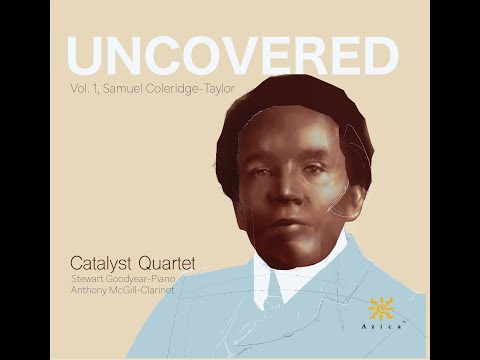

It’s a bitter sign that we’re still living in the era of “firsts” when it comes to Black representation in classical music. The first Black musician to hold a principal chair in the New York Philharmonic did not secure that spot in the first decades of the orchestra’s founding; nor in the explosive heyday of the Harlem Renaissance; nor even in the push for desegregation that accompanied the Civil Rights Movement. Anthony McGill won the position as the New York Philharmonic’s principal clarinet player in 2014, only the third Black player in the orchestra’s history, after hornist Jerome Ashby and violinist Sanford Allen. In his time with the group, McGill has not only won great critical acclaim, he’s also used his platform to be a voice for racial equity in classical music with activities ranging from the institutional to the deeply personal. He recently collaborated with the Catalyst Quartet on “Uncovered,” a new album of works by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, released in February on Azica.

Coleridge-Taylor may well be the most famous late-romantic composer the average concertgoer has never heard of. Born in 1875 in London to an English mother and a Sierra Leonean father, he showed early promise as a composer and quickly rocketed to international fame. By his late 20s, his musical reputation had not only secured him a spot as the youngest delegate at the First Pan-African Conference in London, but also a tour to the United States and a reception with President Theodore Roosevelt. His trilogy of cantatas on Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha rivaled “The Messiah” in popularity and number of performances, and he was greatly in demand as a conductor and competition judge. And then, at just 37, he tragically died of pneumonia. His death has been frequently attributed to his frenzied state of overwork, necessitated by the perpetual precarity of his finances.

But Mozart died at 36, and his works are ensconced firmly in the classical canon. Coleridge-Taylor’s graceful melodies, lush harmonies, and transparent forms would seem to make his music a shoo-in for a place in the standard repertoire, bolstered as it was by widespread popularity during his lifetime. What accounts for his fall from fame?

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

McGill didn’t mince words when I asked him this question. “I don’t think it’s going out on a limb to say that racism in the world creates these kinds of situations,” he said. “It’s whitewashing history: We don’t find out about all the heroes and creators that are of African descent. Without going in too deep, that happened a lot throughout history.” History books often highlight those who most closely resemble their authors—or those their authors aspirationally identify with—leaving many crucial stories sidelined. “It’s a disaster,” McGill added. “It’s terrible.”

One aspect of this disaster is excellent music going unplayed. “Not only is [Coleridge-Taylor’s music] luscious—it has that romantic feel—it has sounds I can relate to as well. It sounds like the experience of someone I can identify with, someone who’s a Black man. Those melodies are singing to you directly, whoever you are. But also, as I was playing them, I felt like they were coming directly from me.” McGill’s experience of playing Coleridge-Taylor’s clarinet quintet seemed to almost go beyond language—he spoke of feeling like a vessel for the music in words that bordered on the spiritual. (His playing on the recording—lyrical, generous, warmly effusive—has a similar kind of captivating power.)

This sense of channeling the music instead of having to go and hunt for a compelling interpretation is certainly a boon for a piece like the Coleridge-Taylor Quintet, a work where there’s no mainstream performance tradition to turn to for inspiration and guidance, nor is there a living composer to ask questions of. “One of my methods of working on a piece is I listen to the actual music; to what the composer is telling me, or, in a way, whispering to me through the music. I listen to the music while I’m playing it, and that’s where I get that communication.” McGill clarified that he’s not making any claims of mysterious insider knowledge: “I’m probably putting my own ‘stuff’ on it, but that’s where I get a sense, even though the composer’s not around, I’m hearing what the composer might have liked. And that will change, of course, over time as I play the piece more and more, what that language is that the composer is whispering to me, but it just has to do with the language of the sound.”

McGill approaches more canonic works this way as well. “Even in more standard or classical pieces, I’m not going to say, ‘This is exactly how you should play this!’ I have the opportunity to create in a personal way that tries to be true to what I feel the composer is whispering to me. And this is for both composers alive and dead! It deserves that energy.”

The continuity of McGill’s approach underscores the continuity of the underlying music. Those opposed to diversifying the classical repertoire sometimes make it seem like all non-canonic pieces are fundamentally Different from more familiar works. Of course, some of them are (and some of those very Different works are amazing). But in the end, it’s all just music; part of the same rich cultural tapestry. The canonic works aren’t the best of the best, they’re just the most famous, and it’s not a coincidence that fame correlates so tidily with structural power. Venturing outside the canon doesn’t mean sacrificing musical quality for diversity; it means finally giving the many brilliant minds who were unjustly excluded from the standard repertoire their due.

The question of diversity is one that has very real consequences in terms of who can imagine having a place in this field, as McGill’s own story bears out. Growing up, McGill had the chance to play in majority-Black community orchestras in the South Side of Chicago, and to study with a number of Black mentors. “Often, we would do pieces by Black composers, so I wasn’t at a loss for the fact that there were these great Black composition heroes when I was growing up,” he recalled. “The Chicago Teen Ensemble would play Bach and Mozart, but we’d also play Duke Ellington arrangements and Scott Joplin, so it wasn’t foreign to me.” If you make diverse repertoire a normal part of the musical landscape, it won’t feel out of place at all.

McGill is doing his best to pass this experience on to the next generation of musicians through his position as the artistic director of Juilliard’s Music Advancement Program, which makes a special emphasis on reaching out to young performers from underrepresented backgrounds. “Part of our training now is to build up the players, not just in terms of down-the-line, ‘We want you to be better at your instrument’; but also in terms of, ‘How do you make a difference in your community? How do you make the world a better place through your art?’” McGill acknowledges that, while he personally feels that he got a fair amount of this in his own education, he knows many in his generation didn’t, and he’s gladdened by how enthusiastic his students seem about this kind of training. “This kind of training gives kids a sense of purpose, a sense of community. I think a lot of kids are really excited by that concept.”

Nevertheless, the Music Advancement Program is just one project, and it can only serve so many students at once. And even then, there are obstacles in the wider world—McGill mentioned the cost of summer music programs as a particular recurring hurdle. This points to larger structural inequities in classical music and beyond.

As the Black Lives Matter movement took to the streets across the country this summer, many orchestras, opera houses, and other musical institutions posted statements in solidarity with the protesters, or at least with the general position that racism is bad. Many saw these statements as evidence that a sea change was afoot, that classical music may finally be divesting itself from white supremacy. I confess that I was, and am, somewhat less optimistic about the depth of commitment these statements represent. It’s easy to post words, but harder to fundamentally change unjust power structures. Could these statements truly presage a meaningful change?

“I think we’ll have to see,” McGill said, considering this question. “I’m not going to assume anything about any one group, but I do know it’s going to be very obvious who has performed in that area, who has taken baby steps, and who has taken large steps.” He did see some reasons for optimism, citing the large number of people “who know what empty statements look like,” which may lead to some organizations quickly emerging as those that “are gonna step into the future.” But he was not without reservations, either: “In a few years, for some 2020 will be a distant memory. Some have probably moved on already.”

In speaking about these changes, McGill talked about increasing the diversity of classical music, but he also underscored the need to increase excellence and beauty. With recordings like “Uncovered” and initiatives to diversify the repertoire, is the goal to build a better canon, a better set of standard works that everyone should know? Or is it to get away from the idea of a canon altogether? For McGill, who relishes premiering contemporary works while also holding a principal chair in an orchestra once led by Mahler, the answer requires some nuance.

“If you talk to me tomorrow, I might say something different, but you know, we have a canon already and that has gotten us where we are. I like music. I like to not necessarily know what’s going to happen. I like playing and listening to pieces that I know, but I also like playing and listening to pieces that I don’t know.” He compared this approach to moving through a gallery of paintings: “As much as I love certain styles of painting and painters, when I go into a museum I think it’s interesting to pause by those artists that I don’t know; to pause and to explore what that experience is. I think we can do that in classical music too.”

As often as classical music is described as having a “museum culture,” this isn’t an experience most classical music presenters necessarily make room for. Indeed, next to a typical orchestral season, even a relatively staid museum looks wildly experimental. Art museums regularly make room for the iconic while promoting the unknown, putting up shows of unfamiliar works from the past and present in adjacent wings to their displays of beloved masterworks. In the same building, one can regularly see art from the Renaissance to the present day. Not so with most classical music presenters, whose “museum culture” is much more restrictive and unchanging. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

“I think there’s an opening for us to create an installation that is artistic, that is musical, that is interesting, that is not necessarily what we expect,” McGill said. “But we have to build that over time, because so many people have come to expect the other thing. We have to trust and expect that they’ll be interested in these kind of explorations of art.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.