In the studios at Maida Vale, the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers are warming up for a world premiere recording. It’s an opera that once graced the stages of Covent Garden in London, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and the Berlin State Opera. But the piece has gone without a professional performance for over a century. Now it is completely unknown. The orchestral score was never published—some of the parts are the same hand-written manuscripts that were used by Covent Garden in 1902.

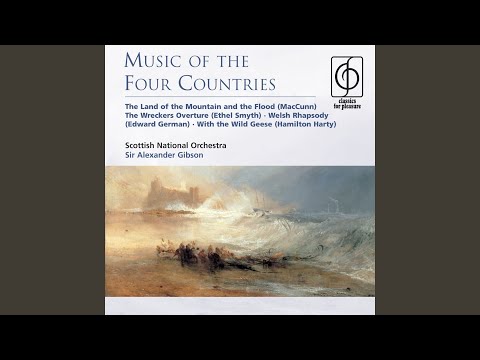

The opera is “Der Wald” (“The Forest”) by Ethel Smyth, who is currently experiencing something of a renaissance. It began in the 1990s, when conductor Odaline de la Martínez performed and recorded Smyth’s third opera, “The Wreckers,” at the BBC Proms. In 2022, both Glyndebourne and Houston Grand Opera took up the opera, and in the last few years there have been new recordings of a plethora of Smyth’s chamber works, from the String Quartet in E Minor to the Suite for Strings. The 2020 world premiere recording of her last major work, a symphonic cantata called “The Prison,” won a Grammy.

This recognition has been a long time coming. For a composer of Smyth’s stature, it’s astonishing that so many of her works are only now being recorded. Born in 1858, Smyth became one of the most important British composers of the early 20th century. She wrote six operas, and critics saw her “laying the foundations of a truly national school of opera” decades before Benjamin Britten came on the scene. By the time of her death in 1944, she had accrued a whole host of accolades, including a damehood for her services to music and three honorary doctorates for composition.

Despite Smyth’s fame in her own lifetime, her music all but disappeared after she died. “There weren’t performers or conductors championing her music after her death,” explains Dr. Amy Zigler, an expert on Smyth. “She was simply forgotten.” There were many reasons for this, not least because Smyth’s style felt old-fashioned by 1944. But her gender was surely one of the most important factors. After all, there were plenty of male composers whose styles can seem “old-fashioned” who not just survived but thrived through the 20th century, like Puccini, Rachmaninoff and Vaughan Williams.

No matter how much Smyth achieved, her music was never heard neutrally. She was always a woman first and a musician second. In 1931, “The Prison” was deemed to show “little evidence of real musical talent.” Critics speculated that it would never have been performed “had its composer been a man and not a woman.” When her Mass premiered in 1893, reviewers slammed it as an example of “ambition which overlaps itself” because the music was too “masculine and vigorous” for a woman. The piece was not performed again until 1924, when it was conducted by Adrian Boult, who said that “its power and beauty impress me more and more every time I touch it.” Then, critics admitted somewhat sheepishly that the Mass had been misjudged at its premiere. The Daily Mail went so far as to say that its dismissal was “stupid and unjust.” It still had to wait many decades for its first recording, but it is now one of Smyth’s better-recorded works, receiving considerably more favorable reviews than in 1893.

History has found many creative ways of dismissing women composers: because they were too feminine, too masculine, too modest, too sensual, too famous, or not famous enough. In Smyth’s case, she was too much of a personality. She was, by any accounts, an extraordinary woman who lived an unusual life. Her list of friends and lovers reads like a who’s who of the Victorian era, from suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst to writers Virginia Woolf and Edith Somerville, the Empress Eugénie and Winnaretta Singer, Princesse de Polignac. And Smyth wrote about them all, candidly, in her eleven books, most of which were autobiographical. “My mother had told me often it was bad manners to talk so much of myself,” she confessed, “but I found the subject so absorbing that I never cultivated the opposite art.”

Everything Smyth did, she did to extremes. One of the most circulated anecdotes about her was that while incarcerated in Holloway for her involvement in the suffrage campaign, she conducted her fellow prisoners in a rousing rendition of her anthem “The March of the Women,” beating time from her window with a toothbrush. She always had a large dog in tow—either her half St. Bernard called Marco, or one of her seven successive Old English Sheepdogs, each called Pan. “Everyone has his own Ethel Smyth story,” one of her friends wrote, “and they are mostly true.”

Without her “iron constitution” and “fair share of fighting spirit,” as she put it, Smyth might never have achieved the things that she did. And where eccentricity was often embraced as a sign of genius in men (Beethoven being the most obvious example), Smyth’s charisma was also used as a way to belittle her. The process of writing Smyth out of musical history began with her obituaries. “She will ultimately rank as a brilliant author and remarkable character who also made some stir by composing music on an ambitious scale for a woman,” The Musical Times decreed.

Over the coming years, Smyth was worse than forgotten. With no recordings or performances to allow listeners to judge her music for themselves, she became a caricature. If she was ever mentioned in the press, it was not as a composer, but as an amusing anecdote—a situation exacerbated by the publication of Woolf’s diaries and letters. Although the two women were close friends, they often fought bitterly, and Woolf could pen devastating character assassinations when she felt so inclined. In Woolf’s diaries, Smyth was “a well-known imposition upon conductors,” who looked like “an unclipped & rather overgrown woodland wild beast, species indeterminate.” The widespread availability of these vignettes—with none of Smyth’s side of the story—only entrenched the perception that Smyth was little more than a funny footnote. As one reviewer put it in the 1970s, “the almost self-parodying Ethel Smyth is rarely taken seriously.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

If Smyth is going to stand any chance of being restored to music history as a composer rather than a caricature, recordings are vital. “Good recordings allow us to evaluate the work, to listen to it multiple times, and to really absorb it,” Zigler says. It’s impossible to get the measure of a composer if only a handful of their works are available to play and to hear. Sitting in on the “Der Wald” recording, just a few scenes told me that this is a very different opera to “The Wreckers.” There are some similarities: both, for example, revolve around a love triangle, and explore how three central characters interact with their surroundings and their community. In “The Wreckers,” Smyth takes us to a poverty-stricken Cornish village where the drama is driven by two lovers betraying the other villagers. In “Der Wald,” we are in a forest; the plot focuses on a young woman called Röschen, her lover Heinrich, and the witch Iolanthe who desires Heinrich for herself. But Smyth’s music is both more restrained than in “The Wreckers” and—somehow—more intense.

“The sheer dramatic concision of it seems to me rather remarkable,” the conductor John Andrews tells me. It’s a one-act opera that only lasts around an hour, in which “the emotional temperature is held at or near boiling point for huge stretches.” When I’d played through the score myself at the piano, I couldn’t understand why the 1902 London critics had placed it as belonging to “the most modern school” of composition. But hearing the piece in full, it’s clear that so much of the work’s power comes from the orchestration, and the dramatic interaction between the three main characters. Smyth uses different timbres for characterization (the bass clarinet associated with Iolanthe stands out), and the writing for Iolanthe in particular is breathtakingly difficult, requiring the singer to traverse an enormous range with power and clarity. The dramatic concision of the opera “almost prefigures the expressionist operas of the following decade,” Andrews says.

Puccini’s “Tosca” had premiered only two years before; Debussy’s “Pélleas et Mélisande” had just been performed; Strauss’s “Salome” was yet to be written. It makes sense that critics heard this work as both modern and daring. The sheer power of the combined orchestra and voices is intoxicating. “This is somebody who knows Brahms and Tchaikovsky, but is also living through the very rapid musical changes of the first decade of the 20th century,” Andrews continues. She “juxtaposes a fairly conservative, late 19th-century, rich, sensuous, Romantic idiom—depicting the forest and the people living and working there—with a much more angular, dissonant, almost expressionist language which she uses to convey the dark, supernatural forces that bring chaos and destruction.”

This opera made Smyth the first (and, until 2016, the only) woman to have had an opera staged at the Met. It was also one of the very few English operas to receive a professional staging in England in the early 20th century. It is a phenomenally important piece of both operatic history and women’s history. And it’s significant for Smyth’s story too. “Der Wald” received such fiercely gendered criticism that it prompted Smyth to begin thinking of herself as a possible feminist figurehead for the first time—a realization that would lead to her eventual involvement in the suffrage movement, composing works like “The March of the Women” that became the anthem for the Women’s Social and Political Union. She told her lover Henry Brewster that she felt she “must fight for ‘Der Wald’” because “in my way I am an explorer who believes supremely in the advantages of this bit of pioneering… I want women to turn their minds to big and difficult jobs; not just to go on hugging the shore, afraid to put out to sea.”

Musically, too, “Der Wald” is vital for understanding Smyth’s compositional development. There are passages when the harmony foreshadows what’s to come in “The Wreckers,” and her nods to Mendelssohn in the Prologue seem to prefigure her later neoclassical opera “Fête Galante.” How it relates to her earlier work, though, is a harder question to answer. Many of her student pieces remain in manuscript only, and her first opera, “Fantasio,” is still in need of its world premiere recording, as is her 1888 cantata “Song of Love,” which has never been performed at all. We’ve still got some way to go before we can be familiar with all of Smyth’s works, to say nothing of her very many contemporaries. This recording of “Der Wald” is another important step towards allowing us to remember Smyth for who she truly was: an exceptional personality, yes—but also one of the most significant and original British composers of the last century. ¶

“Der Wald” will be released on the Resonus label in the autumn. The BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers are conducted by John Andrews, with soloists Natalya Romaniw, Claire Barnett-Jones, Robert Murray, Morgan Pearse, Matthew Brook and Andrew Shore.

Update, 2/24/2023: A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers as the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus. VAN regrets the error.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.