Evan Johnson is a composer; he thinks about sound. But Evan Johnson is also the rare composer who thinks just as much about sight. It’s true that, to the ear, his music is often extremely affecting in its tightrope delicacy, but that aural richness is only a happy consequence of an opulent visual field: his handwritten scores are a lush and private world unto their own. As in: There’s more to this than meets the ear.

“I’ve always maintained,” he tells me, “that the important thing about the piece is not entirely what it sounds like. There’s more to music than that. Sound is only one way of getting at a piece, something it can be productively or interestingly reduced to, though it will always be a reduction. Notation—the score—is capable of more. I think somewhere between Bach and Beethoven we lost the idea of music as more than the sounding surface of the performance. That’s something I want to bring back.”

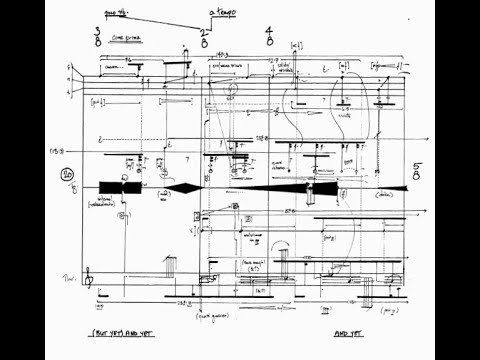

Seated on the outside, his audience are always already voyeurs, peepers to an insular activity or ritual of which they’re only catching spare bits and pieces. The performer is his sole intended listener; face-to-face with the score, they’re the only person in the room with access to the total work. They alone know how much is written on the page, and know—they must reconcile the fact—that there is no way for the audience to hear it all. Johnson asks for the impossible. Performances will always amount to a paltry effort at realizing the utopia of his heavy-laden notation, where the utmost threshold of difficulty is posed to the musician in layer upon layer of detailed minutiae. His is an oppressive generosity, a demanding and insurmountable control that gives bountifully as it takes everything away. The fragile sense of loss that characterizes his music begins at this moment of erasure: when something is always conceded, unachievable, inaudible, concealed between the body and the score, what does remain shivers with necessity and abandonment, lonely between the arid crags.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

“Excess used to be one of the things I would trot out as an axiom of my work, but the emphasis has shifted over the course of my career,” Johnson says. “It’s become now a matter of not just sheer excess, sheer overloading of the performer/victim with circular things that cause them to convey stress and discomfort (though I’m still wedded to the idea of over-notation and fetishistic fussiness, and still think of the material of a piece as every tiny squiggle of ornament, phrase length, Italian performance indications, all the little details). Recently, instead, it’s become a question of activating empty spaces, of keeping spaces open between events. The virtuosity shifts from the simple execution of the material to a virtuosity of long-range thinking, of connecting things that are very far apart. It’s a virtuosity of concentration, a virtuosity of gesture: the state of grace in the extreme state of attenuation.”

Johnson has a work for solo voice called “A general interruptor to ongoing activity” that has, for this very reason, become something of a litmus test for new music singers. The question is not if you can sing it. No one can. The work is by nature a proposed impossibility, with each of the discrete musculatures of the vocal mechanism—folds, tongue, teeth, breath, lips—drawn and quartered into a stave of their own, then funneled through a series of superimposed canons whose competing simultaneity occludes the successful execution of any single parameter. The question is not if you can do it but if you can think it, if you can sustain the intense control and critical intentionality necessary to communicate its shrouded, failed grace. Each time it is an exercise in trust. You dive into that black water with no knowledge of the bottom, never sure of just what will emerge from beneath the unbearable, airless pressure. Your only buoy is the promise of his words, that the tension of autonomic failure is somehow the music’s virtue.

It is an impossible sensation to master, I tell him.

That’s the point, says Evan.

“I gave a talk in Leeds last year about writing music that refuses the idea of mastery: music that doesn’t seem to know what it’s doing, music without confidence in how it’s going to get to the end from where it began, both in a large-scale formal and local gestural sense,” he continues. “For example, my piano piece ‘mes pleurants’ has this constant stuttering, constant stumbling. The cantus firmus in the background moves very slowly, and so with every attempt to get from one pitch to the next, there’s always a bit of struggle, of unsureness as to whether or not it will happen. The way the instrument is played, too, has lots of half-pressure attacks and flicks and clicks, things that don’t quite sound, things that sound very softly, things that sound unpredictably—it becomes a question of confronting a difficulty that is also anti-virtuosic. Classical virtuosity is about hiding the limitations of the instrument, making it seem as though a violin is capable of everything; here, it’s as if no one is capable of anything. That’s not to say there isn’t virtuosity; I’m well aware that, even as the music gets spare, it remains intensely, intensely difficult. But it’s now about a virtuosity of whatever the opposite of virtuosity is, a virtuosity of complete naiveté.”

I perk to hear him talk about confidence or lack thereof. I am beginning to glimpse a tentativeness in Johnson that parallels his music. Unlike much of the “Complexity” collection to which he’s too-often aligned, there is nothing brash or perversely confident about this person. He is exceedingly quiet, self-effacing, and frequently unsure. He mumbles. To everyone but himself he extends an extraordinary kindness and often unexpected charity of energy and attention, but in his own work he is wary, critical, and doubtful—as the music often is—to the very limit of inaudibility. With a dejected and melancholic shrug, he tells me he’s just happy if a performance wasn’t an abject failure, and in a flash, I’m reminded of the final bar of “general interruptor.” A trailing whistle bleeds over that double-bar, floating residue of a run-down system that has nowhere to abandon its ruins except in the attendant abyss of amniotic silence. As it crests the structural threshold, the whistle blooms, ever so slightly, before dissolving, and tucked at the peak of that hairpin is a tiny Italian instruction: quasi apologetico, (poco disperato?)—as if apologetic, (a little desperate?). “I’m sorry; I don’t know how to say this to you, but I’m trying”—“here, it’s as if no one is capable of anything” (though they’re doing their absolute best).

The man is like this too.

Except Evan and I aren’t alone. This is an interview with Evan Johnson, yes, but sticking close to the etymology of the medium—interview from the French s’entrevoir, meaning glimpse—I haven’t shown you everything. At the moment, Evan is talking about instinct: there are two vocal solos on his new portrait CD—“Indolentiae ars,” released on Huddersfield Contemporary Records on November 23—that were written without any pre-compositional planning, a rare turn away from scrupulous calculations for a composer who has defined his work by its rigor for a near quarter of a century—

“…but I’ve found myself in the last five or six years getting a lot more instinctive. I think it’s a symptom of knowing better how the material is going to behave and feeling more confident in the connection between what I’m doing in my pajamas at my desk and what the sounding result will be. 15 years ago or so, I was still under this very American modernist ethical injunction that if an event can’t be justified then it undermines those events that are, that everything has to have a reason. In hindsight, those ten years of pre-compositional obsession were a symptom of insecurity—as, I suspect, they were in the ‘60s and ‘70s for Milton Babbitt. Trying to do things totally ab nihilo, you have to have something, even if you bury that arbitrary decision as far as possible underneath consequential chains of mathematical logic. The generous way of saying it is that I’ve been continuously building that something for myself and now I finally feel as though I can live in it more freely…”

—and never once does Eugenie Brinkema take her eyes off her husband. Even on the technical subject of compositional logic and generational modernism, she attends to his every word, drinking of him with a rapt tenderness that is prepared always to offer insight but never prone to interruption. Only when she’s absolutely sure he’s finished does Brinkema shift her weight slightly, lowering her arm to the table and tearing with some effort her glittering eyes away from her husband’s face. Unmoored, they swivel over her shoulder and settle on me, narrowing in mock-cahoots.

“That’s really surprising for me to hear,” she says, “because if there’s a flat surface anywhere near Evan, he takes it over. In every house we’ve ever lived in, his is the room the children aren’t allowed in because he keeps two or three desks covered in pre-compositional material: graph paper, drawings on the wall, elaborate diagrams, colored pencil markings, sketchbooks. I’ll often go through them and ask him what they say; sometimes he knows, sometimes he can’t remember. But in all this time, I’ve literally never heard him say that he just sat down and wrote something.”

Moments like this are why I invited her, why Brinkema has spent her Wednesday seated happily at her husband’s side. Derrida was fast to point out that if you split the etymology of interview one degree more, you end up with seeing-between. When it comes to seeing in the between-space where the artist and the art become blurry, there is no one in the world more qualified than her. A media theorist best known for her work on horror films and radical formalism (laid out in her two books, 2014’s The Forms of the Affects and 2022’s Life-Destroying Diagrams), Eugenie Brinkema wields a trademark combination of ruthless erudition, dazzling wit, a dizzying command of philosophy, and a mastery of formal extravagance to rival Derrida himself on his best days. What she does, more than anything or anyone else, is play. It really doesn’t matter whether she’s writing about the Final Destination franchise, experimental queer porn, or austere French art: her work runs blistering circles around the dry sexlessness of academic scholarship, basking in its sharp-edged tongue and marveling at its own referential dexterity. Theory is her sandbox. The rest of the world is still hauling crude mounds; she’s torching fistfuls of sand into glass, iridescent and deadly.

In almost every way, Brinkema is her husband’s inverse. This morning, she frames her shock-blonde ringlets with an electric-green knit sweater that clashes blindingly with Johnson’s scruffy muted grays and scarf-wrapped burgundies. She speaks a thousand miles a minute, leaping between the peripheries of seemingly unrelated ideas at a breakneck, fearless pace; tomorrow, I will be forced to slow the recording down to catch her. She is lurid where he is subtle, brazen where he falters, sharp in all the places he is indefinitely grainy. Even in their work—which shares, despite the medial differences, a consuming fascination with the detail—their priorities are often distant. Earlier, he waxed about virtuosity; she rejects it offhand:

“I would never use the word virtuosity, but I love the word dilation. I’m really interested in the capacities of contraction in my writing and thinking. ‘26, more or less’ [her text on the French artist Sophie Calle] is a Lover’s–Discourse-style abecedarium about love: a grand metaphysical idea contracted to a small form. Life-Destroying Diagrams is a maximalist book concerned with how much dilation you can offer to the closest of close readings, to the point that one detail can occupy as much as space as you give it. I like that idea of a kind of maximalism, which I guess is a form of excess. But it also works in reverse: my new book is about color and also about death, both of which are massive topics, and it’s going to be really short.”

For all the difference, though, there is no better interlocutor for his work. Notice, in her earlier comment, the nuanced generosity of her perception: she reveals something both fundamental to his artistic practice—that he has never before written spontaneously—and intimately humanizing. She is attentive to the significance in daily mundanity that only a spouse knows how to spot— like the drawings on his wall, a thread Evan will pick up later.

“I found myself in the last few years obsessively drawn to pencil drawings,” he says, “because of the touch of the hand, the absolute, immediate—literally im–mediate—way you can see the trace of the hand upon a slightly rough piece of paper. I think my work is fundamentally about maintaining that trace of the human.”

Of course she knew their importance. At the moment, his workspace is kept watch by Rembrandt’s “St. Jerome by the Pollard Willow,” Jan van Eyck’s “Saint Barbara,” and a copy of one of the Burgundian pleurants from the Rijksmuseum. (The Dutch preference is hardly a surprise; the family moved to Amsterdam last year.) That all three are pre-17th-century is no accident, either. When I press about his affinity for historical sources, Brinkema lets out a giggle before Johnson can answer.

“How much time do you have?” she warns, jocular, affectionate.

He smiles at the both of us, somewhat unaccustomed to the attention.

“Well, I think of myself as a medieval composer, and my image of what it means to write music is rooted in a 14th/15th-century idea of music written for secrets, for puzzles, for intellectual speculation. On top of that, there’s all the particulars. Everything I do on a gesture-to-gesture basis I also think of as having some sort of medieval precedent.”

Always ready to tie things together, Brinkema jumps in.

“We share this relationship to history,” she says. “If Evan was handed a music department today, he would make people learn to write canons, and I would make people read Aristotle. I think that matters. You can’t know what’s weird about your own work if you don’t have foundations in history or have a basis in rigor, and then you can’t appreciate what you’re doing, which means you can’t do it again, you can’t play with it or build on it. I guess we’re both old-school in that way: education is important to doing experimental work.”

In the mumble-sprint rhythm of their back-and-forth, they will comb through a short list of shared sensibilities: belief in discomfort as an aesthetic starting point; hermeticism as a default working mode; interest in details; the importance of never doing the same thing twice. They will not mention love. Though it is written everywhere in their voices, they will not say the word “love.” I am surprised.

To trust your own abilities enough to push material to its shuddering, violent edge, and then a little more beyond that; is that not love?

To wager again, under threat of futility, an attempt at articulation that will inevitably end in loss, but has something worth losing: is that not love?

Perhaps, to one another, they do not have to say it: love is implied, their first foundation, an ever-present unspoken. But I am here, on the outside. So I pry, gently, about love:

“Tell me about the moments that resonate most with you in the other’s work.”

Twin smiles at the question. Evan speaks first.

“‘Burn. Object. If.’ [Brinkema’s paper for the 2011 World Picture Conference] was probably the earliest,” he begins. “It was one of the first pieces you wrote that was wildly experimental in form, one of the things that tipped over from ‘she’s really smart, she can write well’ to ‘there’s something else going on here.’ ’26, more or less’ [her Calle text, all about love (and dedicated to the one who knows who this is for)] is similar: the combination of absolute rigor—formal extravagance followed through in a rigorous way, consequences be damned—and the ability to pack real emotional wallop.”

He adds, “I’ve probably read every word you’ve written in the last 20 years—”

Brinkema nods; it’s not hyperbole. Earlier this morning, she revealed that Johnson was the first reader for both of her books. (“Both times, when the proofs came in, Evan took the manuscript, read the whole thing through, took notes, and handed it to me. Then I read the whole thing through and made my notes on the pages he’d made his notes on. It was this really beautiful act of love.”)

He continues, tugging absently at his scarf: “—and while I often don’t know what she’s talking about—I don’t have any training in philosophy or media theory or aesthetics—what I can do is read. So the things that I find incredibly striking and valuable are in some sense vaguely academic, but they’re also—without being maudlin, without being autobiographical, without being all-about-her—just incredibly affecting on the level of the reader. I tend to really love the things that embrace a musical or poetic sense of rigorous limitation without losing soul.”

She gives him a playful doe-eyed pout and rubs his knee affectionately.

“Awww. Thanks man.”

I can’t help my giggle: beneath the erudition, Johnson and Brinkema are a pair of college best friends who’ve grown up only in age. I am often reminded that their teenage spark of first puppy-love is still very much alive.

Brinkema sits up brightly, turning to face me head-on (she’s done this each time she talks about Evan in the third person), and dives straight in, as if she’s spent a lifetime waiting to be asked.

“I have a couple of favorites,” she says. “‘Ground’ [Johnson’s 2010 contrabass clarinet solo] was one. When he said he was going to work with ‘Stormy Weather’ as a source text, my first response was ‘What will that even mean?’ And what he ended up coming up with was just so absolutely weird; I could hear the source material without actually hearing it, and it was so beautifully built into the structure. I remember getting to the end of it and realizing I hadn’t even breathed; I’d never heard such a long line maintained. And isn’t that what it’s about? ‘Stormy Weather,’ it’s about the feeling of a melancholia from which you can’t get unstuck. Evan might hate this because he’s not a sentimental or emotional person, but I really remember thinking ‘that’s what it feels like, to feel gutted, wedded to the world, unable to get going, incapable of breathing.’ By the end of his best pieces I realize I’ve been holding my breath and I feel sick in a good way; that’s quite extraordinary.

“And then ‘general interruptor,’ of course,” she continues. “I knew that he had notated all these different levels of vocal musculature, and I remember finding it an interesting intellectual exercise, like ‘Dude. Rock on. What a cool thing. How are you going to do that?’ And then I actually heard it, and yes, I could hear a machine being overloaded, but it was also incredibly beautiful and captivating. Secretly, I love knowing the behind-the-scenes, the ‘Raw and Exposed: The Real Scores of Evan Johnson.’ But I remember thinking then that even if I hadn’t known beforehand, I would have known it when I heard it: the complexity, the sense of so many things happening that you can’t catch up to them, and again, this insane sense of fragile, lace-like detail, it’s all there. I love it, I love that piece.”

Brinkema pauses, a hair’s breadth of silence in which she glances sidelong at her husband. There is an unspoken pregnancy to the moment, though the thickness has nothing to do with hesitation or apology. She is not looking to him for approval, neither gauging his reaction nor weighing her words. It is a look both steeled and intensely gentle that says, in a fraction of a second: I see you, I know you are here, and I know how you will respond to what I’m about to say but I also know you trust my love for you, that you will understand what I mean:

“Ev would never describe his music this way,” she continues, “but he doesn’t have to: I find his music incredibly existentially profound. In my own work, I think of theory as embodying a kind of artistic generative practice, and similarly I think of his art as embodying ideas about time, about fragility, about humanness and the way that we relate to things, about constantly trying to start over, never re-finding that origin, never finding an end but constantly making effort. Especially when he writes for the voice, or any instrument with breath as a central component, you can hear the grain of the voice, the texture of the body, the fragility of human finitude. It’s true that sometimes they’re just incredibly beautiful, and you can float along with them, but eventually something will happen to undercut that surface and reveal the complexity underneath. I like things with a beautiful surface undercut by a roiling difficulty; he manages to keep both of those in the air in the pieces I love the most.”

At the best of times, an interview, the between–glimpse, is only a quick simulacrum of love. It demands an approximation of heightened intimacy from both parties, hazarding a vulnerability to scrutiny and perception of the unspoken that is otherwise reserved solely for kitchen table whispers at three in the morning: “show me who you really are,” it asks, with no basis for the safety required to do so; “bare yourself to me” with no knowledge of who “me” is. It is impossible, and terrifying that way, in the way love is.

Only this time, it’s not a simulation. This is the real thing. Johnson and Brinkema have had this conversation a thousand times, over microwave dinners because there’s not enough time, in college common rooms after everyone else is asleep, in the lingering dimness of post-film cinemas, in first apartments, hospital waiting-rooms, over bleary-eyed breakfasts when the kids won’t sleep, in long emails written mere rooms away because I need to say this to you now before it slips my mind, in bed, my head on your shoulder. Every word, every ounce of articulation pored over again and again together, each inflection packed with the significance of time. “I know what you are saying, even when you don’t say it” is another way of saying “I love you.”

Which, I guess, makes me the audience, the glimpsing voyeur. Here I am, seated on the outskirts of a lovers’ discourse, desperate to attend to the inscriptions each has left upon the other. In smile-lines and the way hands brush beneath the table as though I wouldn’t notice, in the wordless jut of a chin, eyes flashed in recognition, soft exhale, I see the pathways of exchange unfurl in rivers across these bodies which are for one another in life as much as in work. And yet, still, I must inevitably face the blunt and radiant truth, that there are things which pass between these two that will forever remain illegible to me, things which were never mine to know.

I am not not talking about the music of Evan Johnson. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.