The Center for Black Music Research (CBMR) is an independent research unit of Columbia College Chicago devoted to the documentation, research, preservation, and dissemination of information about the history of black music on a global scale. I recently spoke with Melanie Zeck, Research Fellow with the Center, over Skype. Zeck joined the CBMR in 2005, and is also Managing Editor of the Black Music Research Journal, the peer-reviewed journal of the Center for Black Music Research. Together with the CBMR founder, the late Dr. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., she co-authored The Transformation of Black Music: The Rhythms, the Songs and the Ships of the African Diaspora, published through Oxford University Press.

VAN: To start with, I’ll just invite you to give an overview of what the Center for Black Music Research does.

Melanie Zeck: We’re a one stop shop—that is, we house a comprehensive collection of primary, secondary, and sonic materials on music and music-making practices throughout the African Diaspora, as well as the reference materials necessary to help cut through the informational red tape. There’s nothing better than being in an environment where you have access to all of that information within 20 feet of your desk.

Right now, I’m collaborating with conductors and performers in Africa, Australia, Europe, Singapore, and the United States, to help them discover and program music by black composers. With the CBMR’s robust collection, what I’m able to do is say, Sure, we’ve got what they need, but we also have the primary material in the back that helps the conductors and the programmers make the kind of musical decisions they need to make.

We collect everything from cylinders to modern day formats, and as a research center, we have written and produced a lot of research and reference material. Sam [Floyd] used to say that he could remember a time, when he first started working in black music research, when he had read every single book on black music. And when you come to our archive [now], you can see that there’s been an explosion of research, and it’s really exciting when you go to an entire wall of jazz, and then the wall has to be divided by subgenre and area and decade.

He had a policy of purchasing everything he could get his hands on, and he forged relationships with like-minded researchers all over the world. There’s an oral research institute in Malawi for example, and the two men who work there, Gerhard Kubik and Moya Malamusi, are famous for their work on a very specific kind of jazz called Kwela, whose players were inspired by Lester Young of St. Louis, Missouri.

You’re probably wondering, what’s the connection? Well, [Kubik and Malamusi] deposited some of their early field recordings over here. They have stuff in Malawi, of course, but what’s great is that through our collection we can help other researchers make connections. So I’ll get a call from a jazz practitioner in Japan, and he’ll say, “So, what about jazz in Africa?” And I can say, “I’ve got everything you could need, I can get you hooked up.”

In the U.S., we are so focused on the European canon in our system of music education. Most of the schools here who have orchestral or band programs are National Associations of Schools of Music accredited, so they don’t really have to branch out if they don’t want to. A lot of the ethnomusicology programs that do provide access to this kind of material are housed in Africana Studies Departments, or even in English Departments under “folklore.” Music students just aren’t getting exposure to this kind of music. But when they become practitioners, they can come to me, tell me they have an idea, and I can provide them with everything they need.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

The CBMR frequently receives gifts. Has there been anything particularly striking in recent years?

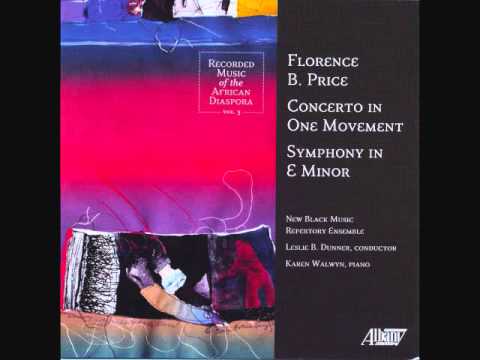

Florence Price’s Concerto in One Movement in D Minor was performed by the Women’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago in 1934, but by 1940 the piece was lost. Totally disappeared. Of course, that included the conductor’s score and the individual orchestral parts. As late as 2017, we have no idea where they are.

My predecessor Suzanne Flandreau started the [CBMR] library in 1990, and over the course of her 22 years sitting at the reference desk, you can’t imagine the kind of long-lost materials people sent to her. She realized that over time, people had sent her gifts of three different versions of the same piece, and she was pretty sure that they were this long-lost piece. One gift was a two-piano, four-hand reduction in manuscript. Then she received what appeared to be the same thing, but was actually Florence Price’s handwritten orchestral reduction. Above the notes it says “fl” [for flute], or “tpt” for trumpet, or “str” for strings. No indication of how many. No indication of which strings. But those were her annotations to herself, and underneath was the real piano part. Then, in another package, Suzanne got a three-piano, six-hand reduction. Still no orchestral parts, still no conductor’s score. So, Sam starts thinking, “I wonder if we can put it back together.” We used to joke around that it was like a musical version of Humpty Dumpty.

They hired Trevor Weston at Drew University, a composer-theorist. He had studied composition at UC Berkeley with Olly Wilson, one of the main heavy hitters in black music in the classical idiom, and also a scholar of Africana Diasporic compositional practices. Olly was born in 1937, so he was among this group of practitioners who were growing up after the Harlem Renaissance, but got all their musical knowledge from those who’d thrived over its course. Sam needed somebody who was familiar with these kinds of compositional strategies and music theoretical practices because they would be necessary for putting a piece back together in the African-American compositional style of the 1930s.

So Trevor assembled this piece—he came to the CBMR, had stuff laid out all over the reading tables. Sam had an ensemble ready to perform it, and we hired Karen Walwyn, a pianist and professor from Howard University, to learn the piano part. We printed Trevor’s reconstruction, had a live performance, and recorded it through Albany Records. [Now] I can barely keep up with the number of requests to rent Trevor’s reconstruction.

What are some research areas you’d like to pursue in the future?

One of the things I’m hoping to explore more is the area of Minas Gerais, Brazil. There’s just an amazingly rich tradition of classical music in Brazil: we’re talking motets, masses, the kinds of genre-specific things we all know from our classical musical training, that were all done by practitioners of African descent, who in many cases were working under the auspices of the Catholic Church, because Brazil was very Catholic at the time. One of the first composers that we talk a lot about was Vicente Lusitano. Lusitano means “Portuguese” in Portuguese, so it’s basically Vincent of Portugal. And he was operating at the same time as Gesualdo, Palestrina. He was in Portugal, went to the Vatican, was working there—he was able to make significant and long-lasting contributions to music history. He was in a debate with Nicola Vicentino around the 1550s, on the issue of chromaticism. While Vicentino actually lost the debate and Lusitano won, Lusitano’s name is never mentioned in mainstream music history books. And we’ve always wondered, was it an issue of race, that he wasn’t included in these musical stories?

One of the questions that we field all the time is: if you take someone like Lusitano, who is the earliest person to be mentioned in the International Dictionary of Black Composers (which Sam was also the editor of in 1999), you want to include him in all of your lectures on classical music—are you including him because he’s black? We get questions like this all the time. And it gets very sticky. I’m sure your readers will understand that black musics have been avoided—they’ve been marginalized, they’ve been left out.

Musicology has long gone past the idea of discovery and positivistic research and since 1985 has really launched into critical theory, literary theory, all those kinds of things, without ever including and going back to the discovery phase of black classical music. So much of our work walks the fine line of continuing to make new discoveries while also trying to infuse black music into mainstream music courses and texts. That requires us to be able to have competent, intelligent conversations using literary and critical theory. But at the same time, I get people from all over the world who’ve been in their grandma’s attic, or went to a church and found something—they’re always wanting to donate materials. The discovery phase for black music is so far from being over.

Can you share an example of what kinds of things are uncovered?

One day, I was contacted by someone wanting to know about her childhood piano teacher, Muriel Rose. I keep files on everyone and I looked through them—no Muriel Rose. I started searching for anything that could tell me who she was, what she tried to do, where she was operating, and when she was most prolific. No luck. Then I got the idea to go through The Chicago Defender archives.

Muriel Rose was listed time and again in the same columns, announcements, and blurbs, as Florence Price and Margaret Bonds.

I started thumbing through my Florence Price files, of which I have a lot. Muriel Rose’s name appears frequently; until that moment I never had reason to ask, “Who is Muriel Rose?” The Defender archives mentioned some of her students, they listed where her salons were, where she was going, what she was doing, who she was playing for, who her kids were playing for. I was reconstructing Muriel Rose’s life right before my very eyes.

Then on another occasion, someone came in and asked for information about Nannie Strayhorn Reid. So I check my files. I don’t see anything. But I go back to The Defender printouts from before, and I had a ton of stuff about Nannie Strayhorn Reid, because she’s listed next to Muriel Rose, who is listed next to Florence Price, who is sitting in my filing cabinet! These women were all operating within a very small geographical region, they were overlapping and intersecting the whole time.

And this was an example of two sets of practitioners coming to the Center and asking a question, prompting me to go further and further back in research I’d already done, [but hadn’t made the connection], because these names didn’t mean anything to me when I was looking at them [initially]. And it really caused me to do some self-reflection and think, “Who else have I missed?”

There are so many angles. Nobody alive today remembers Mozart. At the CBMR you’re working with living people, their memories, their meaningful recollections. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.