I have met Daniel Barenboim twice. The first time was during his first visit to Beijing in 2008; we had a brief chat after a press conference. At that time I was impressed by his promoting peace in the Middle East together with Edward Said, and I have a Chinese translation of the book of their dialogues, Parallels and Paradoxes, at home. I was also impressed by his rebellious spirit dealing with Richard Wagner and Jerusalem, so I managed to convince a publisher in China to buy the copyright of his new book Everything is Connected and began to translate it.

Last summer, I met Barenboim for the second time in London, after his press conference launching a new piano. As we walked down the staircase, he asked for his cigar, and turned to me: “Music has been put into an ivory tower, a result of no music education in schools and no general education in music schools.” He then changed direction: “China is a good example—classical music came to China relatively late, but how it has really developed!” He then concluded: “Music belongs to everybody, regardless of talent, geography…” He seemed to like the idea of being a moral leader.

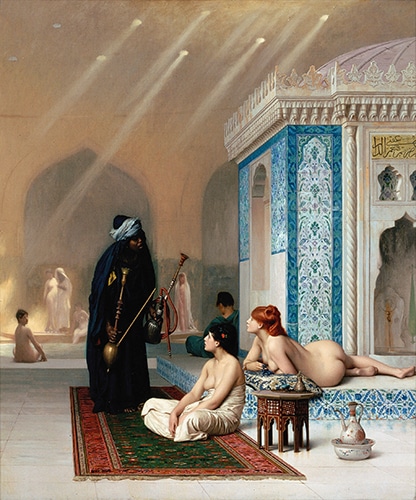

Pool in a Harem; Jean-Léon Gérôme, circa 1876

Barenboim gave a lecture in memory of Said the same evening. He revisited the subject but alternated his approach: “The European governments have made a grave mistake over the last 20 years, when new areas have opened in the world—China, India, Brazil… We all know the Chinese can imitate better than anybody else, they will be able to make a car as good as BMW and Volkswagen but cheaper… It’s better to send the Berlin Philharmonic to play Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 because [that is something] they can’t imitate. Neither the Beethoven nor the orchestra.”

It wouldn’t have surprised me if I heard this kind of talk casually in a pub, but when delivered by a renowned and respected conductor, pianist and activist, at the South Bank Centre’s Edward Said Lecture—“the musical center of the world” according to Barenboim—it deserves to be frowned upon. While I admire Barenboim’s courage and effort in his peace work, and agree that it is good for classical music to reach a wider audience, the intention and attitude in how he achieves this makes a difference too.

According to Barenboim, by 2050, Africa’s potential population of over 1.5 billion people “[wouldn’t] know the first thing about European culture.” This upsets the maestro. It seems to be a potential threat to Barenboim that the prestigious status of Western classical music in the world today might not last for long, and he has determined he will spend the rest of his life promoting classical music in “Ethiopia… Iran, all that.”

This all sounds so familiar to me. When Barenboim named China, India, Africa, and Brazil as “areas newly open over the last 20 years,” I had a flashback to China’s colonial chapters, after the closed door of Qing China was knocked open by the British Empire and its large quantities of imported opium. “Now I want to explore all those places where music hasn’t been brought to.” Barenboim claims to speak in the name of music, but what I see is a glimpse into the mind of a colonialist.

While millions of parents are pushing their children into a “musical star” mass production mechanism, and the nuclear families are becoming more and more the major audience of concert halls in China, the Eurocentric declares that the hope of classical music lies in the East. In Barenboim’s ideal world, musicians of each and every country on this planet should get together and make sure European culture is saved. Barenboim named the two most touching experiences to him in recent years: playing the first book of Bach’s “The Well-tempered Clavier” in Ramallah, and conducting Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 as an extremely rare classical music concert in Ghana:

“They had no idea what it was. …They listened with a silence that I have only heard on very special occasions. They didn’t understand anything about the symphony at all, I’m sure, how could they. But most importantly is that they were in the presence of a very important human statement.” He advocated that all the great European orchestras go to areas that “do not get music.”

Here is the irony. This is supposed to be a lecture paying respect to Said’s life work. The late scholar, Barenboim’s academic friend, was best known for coining the term Orientalism to “criticize a perceived patronizing Western attitude towards Eastern societies that is to justify Western imperialism.” The two founded the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra together in 1999, and their dialogues of “explorations in music and society” were published as Parallels and Paradoxes and have inspired many since. But the idea that Eastern and African societies with rich musical traditions need to be brought music from the West fits quite well with Said’s definition of Orientalism.

When Barenboim advocates European orchestras moving into new markets, they are not filling a vacuum. Instead, they are competing with and in some cases replacing both local classical music ensembles and other, equally rich classical traditions.

In China, as new opera houses and concert halls are built in different cities, governments and corporations fund orchestral concerts played by big names from Europe and the U.S., and the press takes pride in this “emerging market of classical music.”

Three years ago, the major concert halls in Beijing had a big party celebrating the “Gustav Mahler Year.” 10 symphonies by Mahler were performed by seven major orchestras from Europe at the NCPA, the largest performing arts center in Beijing. During the same months, those programs—10 Mahler symphonies in different interpretations by different European orchestras—were also seen onstage in Beijing city, curated by the annual Beijing International Music Festival. It was fascinating to see a “difficult” composer such as Mahler winning gigantic mainstream attention in a country where, by the end of each year, there will still be a large market for tourist-filled temporary orchestras from Europe playing kitsch New Year’s Concerts, winning enthusiastic applause and a full house attendance.

In contrast, the musical seasons of the three major Chinese orchestras—the China Symphony Orchestra, the China Philharmonic, and the Beijing Symphony Orchestra, who have been endeavoring to combine classic European pieces with contemporary Chinese works—are suffering from a lack of devoted audiences, and there is still no solution in sight.

In this process, non-European classical music has been marginalized, including the traditional pentatonic Chinese music documented for at least the last 2,600 years. While I believe that European classical music is significant in the development of humanity, so is every other kind of music that has provided inspiration. As a classical music lover, I am pleased to see this music has reached a wider audience in China; but I am also a little envious of Africa, where the rich and diverse traditional musics are still essential to daily life. Music speaks no genres and classes, it stays alive. It doesn’t need a European messiah. ¶

Comments are closed.