Only then can his creative genius begin redounding, as it should, to the glory of Black music history,” writes the musicologist Robert Stevenson in his 1982 article, “The First Black Published Composer.” Stevenson’s subject was Vicente Lusitano (ca. 1520-ca. 1561), an African-Portuguese priest and musician who enjoyed an international career. Stevenson heralds works like the motet “Heu me domine” (1551), which exemplifies the composer’s unusual embrace of chromatic counterpoint. Listen to the first 1:08 of this stellar performance of the piece by the Australian Chamber Choir to hear the tendencies that make Lusitano’s music so distinctive:

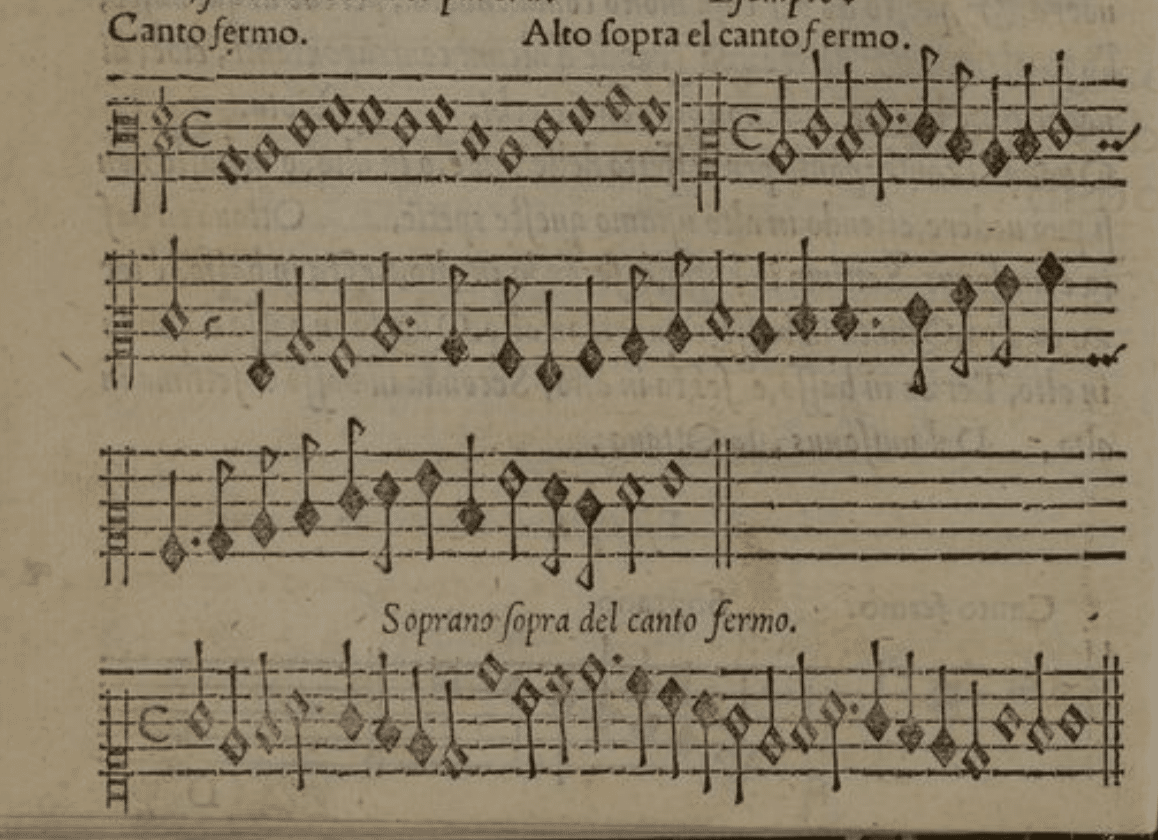

Of Lusitano’s compositions, “Heu me domine” has received the most attention from modern scholars and performers, but it is not the only example of his remarkable creativity. In a 1962 essay, Stevenson reproduces a passage from Lusitano’s motet “Regina coeli” to highlight its adventurous chromatic writing, and notes that other works in Lusitano’s 1551 motet collection feature extremely uncommon combinations of accidentals. Musicologist Philippe Canguilhem, in a 2011 essay regarding Lusitano’s unpublished counterpoint treatise, writes that Lusitano is “particularly tolerant“ of dissonance, a practice he justifies in the text by citing Pythagoras and Boethius.

The alluring counterpoint and voice leading of “Heu me domine” connect to improvisation techniques which Lusitano outlines in his counterpoint studies. As Canguilhem notes, these works make pioneering arguments regarding canons and the productive interplay between composition, free improvisation, and structured improvisation. “Heu me domine” is one of just two pieces in Lusitano’s output that 20th-century scholars have transcribed into modern notation—until last month, it was the only piece of his to be recorded. The other work, a 1562 madrigal called “All’hor ch’ignuda,” was recently arranged for woodwind trio and recorded by multi-instrumentalist Misty Theisen. Though the work is surprisingly tame in comparison to “Heu me domine,” it’s an excellent example of the typical 16th-century Italian madrigal.

Stevenson heralds the “modal daring” of Lusitano’s sacred music, while Canguilhem celebrates the “audacity” of his dissonant contrapuntal writing, yet Lusitano is not remembered as an innovator of Renaissance musical style. Although the first edition of his motet book can be found on multiple online databases, no critical editions of Lusitano’s works have been produced. In a 2017 interview with VAN, Melanie Zeck, a reference librarian at the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center and an expert in Black classical music, identified Lusitano as an important topic for future research. But I never heard Lusitano’s name in nine years of undergraduate and graduate music study in the United States. He also does not appear in recent editions of Donald Grout, James Burkholder, and Claude Palisca’s iconic textbook, A History of Western Music.

The enduring silence enveloping Lusitano’s legacy is particularly poignant today, as 2020 is the possible 500th anniversary of his birth. Classical music institutions often use anniversaries as opportunities to highlight certain composers, but, so far, their appetite for history appears to have nothing to offer Vicente Lusitano and his music. Lusitano’s story shows how composers’ achievements—particularly those with underrepresented identities—can fall through the cracks of classical music’s history-making mechanisms. His silenced legacy puts into relief the gulf that separates the richness of its past from the purported “truth” its institutions portray as history through their performances and scholarship.

Ironically, Lusitano’s obscurity originates in the most famous episode of his career. In 1551, while in Rome, Lusitano was drawn into an aesthetic dispute by fellow composer Nicola Vicentino (1511-ca.1576), an argument which gained so much attention that a Vatican tribunal convened to issue a verdict. Lusitano won, and Vicentino paid a fine, but, for years afterward, Vicentino published egregiously disingenuous descriptions of the proceedings with the aim of damaging Lusitano’s reputation. A 17th-century source in Rome attests that Lusitano’s name was scratched off copies of the widely-published introduction to his counterpoint treatise, and it is plausible he faced other reprisals that went undocumented. These developments likely led to Lusitano’s relocation to Germany sometime after 1553, where he converted to Protestantism, married, and continued his career until his death.

According to a 1551 memorandum, Vicentino specifically took issue with Lusitano’s motet “Regina coeli.” He argued that its writing demonstrated Lusitano did not know the genera he was using: essentially, Vicentino thought Lusitano’s music was too chromatic. In 1555, Vicentino published an account of the debate that was so misleading that Ghiselin Danckerts—one of the judges from the original adjudication—publicly denounced Vicentino’s inaccuracies and fabrications. The American musicologist Henry William Kaufmann revisited the primary sources surrounding this event in 1963, and deemed Vicentino’s account unreliable.

Still, the misinformation campaign succeeded. The scholarship and compositions Vicentino published after his dispute with Lusitano influenced later generations of Italian composers, including Carlo Gesualdo; they also became a critical resource for future studies of Renaissance chromaticism and almost for every reference to Lusitano from the 1700s onward. For centuries, the most accessible and highly-regarded music histories have either omitted Lusitano altogether or only included the scant and biased details provided by Vicentino. The 2006 edition of Craig Wright and Bryan Simms’ Music in Western Civilization I used as a student only mentions Vicentino once. The 2010 edition of Grout’s A History of Western Music specifically celebrates Vicentino, citing his 1555 treatise—the same document his superiors decried as misleading—and the 1572 madrigal “L’aura che’l verde lauro” as evidence of Vicentino’s innovative style.

It’s true that Vicentino’s “L’aura che’l verde lauro” makes heavy use of chromatic techniques—but they seem inspired by Lusitano’s motets, which were published two decades earlier. (One direct chromatic triad progression appears lifted from “Heu me domine.”) Vicentino is an interesting figure—he even conceived a 31-tone, microtonal keyboard instrument—and his works are beautiful and impressive in their own right. But they overlap too much with precedents established in Lusitano’s music—works we know Vicentino heard—to justifiably be considered visionary. The implication is that, while attempting to obscure Lusitano’s artistic and academic legacy in Italy, Vicentino may have also surreptitiously absorbed and reproduced elements of his rival’s musical style.

We know from the documented experiences of other composers with minority identities that generalized prejudice has pervaded the cultural space of classical music for centuries. For example, Lusitano’s Italian contemporary Maddalena Casulana (ca. 1544-1590) used the dedication to her 1568 book of madrigals, which is considered the first composition published by a woman, to excoriate her male peers for sexism she endured. These and many other examples indicate a persistent pattern in the history of classical music wherein composers who are women, people of color, and members of other oppressed populations encounter prejudice and disenfranchisement, cannot access the same channels of power and resources as their more privileged peers, have their achievements minimized and existences denied, and are pushed to the margins of classical music’s collective memory.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Lusitano’s obscurity also shows the influence of collective action on a composer’s legacy. Vicentino worked hard to distort and erase Lusitano’s achievements, but these efforts only retained their impact because other scholars and artists have—perhaps out of convenience or ignorance—uncritically reproduced Vicentino’s version of the facts. Whether any of these developments are related to racial bias is difficult to prove. Nevertheless, composers with historically excluded identities, like Lusitano, have been extraordinarily underserved by institutions of classical music performance and scholarship. Reports from Bachtrack.com analyzing programming from more than 160,000 classical performances around the world between 2014 and 2019 show a population of just 15 white men constitute the 10 most-programmed composers in each of those five performance seasons. Recent research by Philip Ewell exploring the intersection of music theory and critical race theory also compellingly asserts that institutionalized music scholarship is structured in a way that ignores the achievements of women and people of color.

In a 2008 article in Renaissance and Reformation, Kate Lowe notes that Spain and Portugal had the largest populations of Africans in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. By the 1520s, Black Africans in Italy were able to achieve limited assimilation, but genuine acceptance, “as Catholics and Europeans,” was yet to come. The language of 17th-century documents specifically indicate that Lusitano was part-African, part-European, and more recent theories suggest Lusitano’s mother was from Africa. Considering the historical context Lowe provides with respect to the presence of Africans in Europe at this time, it seems probable Lusitano was only one or two generations removed from slavery. That said, the complex implications of Lusitano’s multiracial background are impossible to fully account in this article, except to say he very likely faced racial prejudice throughout his life. Classical music’s history overlaps with European colonialism and the forced diaspora of Africans around the world, and the field’s traditions and biases intersect with the racism, sexism, and other discriminatory practices expressed by the societies in which it exists.

Evidence asserting Lusitano’s race, and countermanding Vicentino’s portrayal of their famous dispute, has existed since the 16th century. The few persistent pieces of Lusitano’s legacy speak to an enduring patchwork history serving generations of musicians with minority identities. Ranging in its forms from personal letters, to manuscripts, to published articles, this record has been routinely ignored by classical music’s traditional artistic and academic enterprise. But this bricolage of informal documentation has been especially meaningful to our current knowledge of composers of African descent.

In the United States, for example, writers, musicians, and activists have created highly detailed accounts of Black musicians and their work since the late 19th century. In 1878, African-American historian James Monroe Trotter published Music and Some Highly Musical People, which gives an encyclopedic account of 19th-century Black classical composers and performers in the United States, including scores for 13 compositions. Maud Cuney-Hare published Negro Musicians and Their Music in 1936. The 20th century saw committed musicians and academics draw tighter connections between each other’s research concerning Black classical music around the world.

As Suzanne Flandreu, the original archivist at the Center for Black Music Research, describes in a 1998 article in Notes, Stevenson published “The First Black Published Composer” in a period of coalescence in this field of music scholarship. The era involved a host of major figures, including Dominique-René de Lerma, Eileen Southern, Undine Smith Moore, Lucius Wyatt, Olly Wilson, and Samuel Floyd Jr., who founded the Center for Black Music Research in 1983. These researchers all held positions within classical music’s scholastic establishment. By publishing new research and producing modern editions of arcane scores, they targeted many of the barriers of entry, or favored excuses, that keep music by composers of African descent out of concert halls and intellectual discourse.

Stevenson wrote his 1982 article asserting Lusitano’s identity as a constructive response to eminent African-American musicologist Josephine Wright’s 1979 paper in The Perspective in Black Music that suggests African-English composer Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780) was the first Black composer to publish music. Stevenson was not aware of Lusitano’s identity until he encountered a 1977 volume by Portuguese musicologist Maria Augusta Alves Barbosa; he also cites a 17th-century manuscript by João Franco Barreto (ca. 1600-1674) as a vital pre-20th-century source affirming Lusitano’s identity. As Stevenson writes, Barreto was commissioned to write an extensive bibliography of Portuguese musicians, but the work was inexplicably disallowed from publication upon its completion in the late 1600s. Although 18th-century scholars had access to this manuscript, it took nearly four hundred years for the implications of Barreto’s research on the history of composers of African descent to reverberate within music academia.

Very little has happened with Lusitano’s compositions since 1982. A handful of recordings featuring “Heu me domine” are available commercially and on YouTube, and new research involving the manuscript of Lusitano’s complete counterpoint treatise began in the last decade. Despite the quality of his music and his place in history, Lusitano’s works remain very rarely performed, if at all, and no new editions of any of his compositions have been announced. A new generation of initiatives and institutions led by musicians with minority identities—such as the Sphinx Organization, Castle Of Our Skins, and the Luna Composition Lab—are making important strides towards social equity in classical music. But, more broadly, resources for accessing, studying, and performing music by composers of color, women composers, and others are declining. The Black Music Research Journal was discontinued in 2016 and, in 2019, Columbia College Chicago announced major staffing cuts at the Center for Black Music Research that put this critical institution’s survival in doubt.

By denying, dismissing, or ignoring the classical music of women, people of color, and members of other oppressed populations, the field of classical music risks replacing documented history with myth and implies that privileged groups lose nothing by excising others from their traditions. These practices also signal the field’s lack of concern for contemporary audiences who share identities with excluded composers. African-American pianist and social justice artist Anthony R. Green, the associate artistic director of Castle Of Our Skins, remembers the jolt of recognition he got when he first heard Lusitano’s “Heu me domine.” It was “a life-pausing moment,” he says. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Updated 6/22/2020. The previous version of this article misspelled Philippe Canguilhem’s name.

Comments are closed.