No one composer, perhaps in the history of Western classical music, was more active in averting history’s prying eyes than Johannes Brahms. Brutally self-critical about his own work and exceptionally shy when it came to his personal life, Brahms sought to preserve his legacy by keeping his private thoughts out of the grips of unforgiving historians. He burned countless early works and sketches—in fact, he burned everything he composed before he turned 19, and that includes at least 20 string quartets. From personal letters to pink slips, doodles to receipts, Brahms left behind virtually no paper trail. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, he went as far as to recall letters from friends he had written to over the years. Clara Schumann, his closest friend, potential lover, and confidant, to whom he wrote countless letters over their 40-year friendship, reluctantly returned his letters, knowing full well Brahms intended to destroy an important, albeit deeply personal, piece of 19th century European musical history.

This makes the delicate task of examining any facet of Brahms’ life, especially something as intimate and mercurial as his relationship to women, enormously difficult. Keeping in mind that virtually nothing remains in the words of the composer himself, we will forge ahead, using the abundant reminisces and first-hand encounters we have from Brahms’ friends and close acquaintances as a starting point to our discovery of his interpersonal struggles with women.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Brahms’ general dislike of women is surprisingly well documented, leading some scholars to label him an outright misogynist. They suspect that this aversion stemmed from his experiences as a boy playing piano for sailors and prostitutes alike in Animierlokale (arousal pubs) in his hometown of Hamburg. While the accuracy of these stories is disputed, they are nonetheless an integral part of the picture Brahms chose to paint of himself and his apparently troubled childhood. A telling anecdote in Eugenie Schauffler’s biography of Brahms captures it all. Max Friedlaender, an acquaintance of Brahms, attended a birthday party for the composer in 1880. After multiple glasses of champagne, the conversation turned to an admired woman known to everyone at the gathering. When Brahms was asked what he thought of her, he “broke out into a horrible, coarse tirade against this lady, broadening out to include women in general, and actually ended by applying to them all an incredible, unspeakable epithet.” (You may only guess.) The party quickly broke up after this sobering outburst and Friedlaender was tasked with walking the now heavily intoxicated Brahms back home. In their conversation, Brahms broke out in another rant: “You tell me I should have the same respect, the same exalted homage for women that you have! …You expect that of a man cursed with a childhood like mine!” Friedlaender summarized how Brahms’ father would “drag him from bed to play for dancing and accompany obscene songs in the most depraved dives.” Brahms, recounting the horrors to Friedlaender, continued, “When the sailing ships made port after months of continuous voyaging, the sailors would rush out of them like beasts of prey, looking for women. And these half-clad girls, to make the men still wilder, used to take me on their laps between dances, kiss and caress and excite me. That was my first impression of the love of women. And you expect me to honor them as you do!”

Brahms was not only mentally affected by these events; he lost weight, became anemic, developed insomnia, and severe and debilitating migraines. Although later in life Brahms described this time as character building, it no doubt had a lasting negative impact on him, precipitating his lifelong antagonistic views toward women. Instead of seeking out meaningful romantic relationships, Brahms sought prostitutes to fulfill his sexual desires. According to Eduard Hitschmann’s 1933 article, Brahms und die Frauen, “the objects of Brahms’ sexuality were only girls of the people, mostly paid prostitutes.” And Brahms was not shy about this fact. In his biography, Schauffler claims that Brahms was indeed “proud of never having broken up households or seduced girls of good family.” When hailed by a prostitute after a concert with friends, he turned to Frau Prof. Brüll, the wife of the acclaimed Viennese pianist and close confident Ignaz Brüll, and declared boastfully to have “never made a married woman or a Fräulein unhappy.”

But there were exceptions to Brahms’ self-proclaimed modus operandi—his relationship with Clara Schumann being the most glaring example. In the winter of 1854, Brahms rushed to Düsseldorf to be with Clara Schumann after her husband, famed composer and critic Robert Schumann (not to mention the 21-year old Brahms’ greatest mentor and supporter) had a mental breakdown and was placed in an asylum. With seven children at home, one in the womb, and her husband bedridden, Clara needed the support of a friend. Over the next two years Brahms went the extra mile, acting as a surrogate husband and father to the Schumanns, taking on piano students to help pay the bills, mentoring the children, and giving tireless emotional support to Clara. It’s no surprise that in these most intensely intimate and vulnerable circumstances Brahms and Clara fell deeply in love.

Clara was, in Brahms’ eyes, not the horribly repugnant image of the immoral and conniving woman he described to Friedlaender on that champagne-fueled night, but rather a nurturing mother figure, a sensitive and intelligent musician, and a faithful wife. Brahms admired Clara for her perseverance despite her husband’s tragic lifelong struggles with mental illness. In a letter to his close friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms professed, “I love her and am under her spell.” After Brahms broke off their relationship in 1856, the two stayed close, building up an extensive correspondence over the next 40 years. Despite their ups and downs, Clara and Brahms rarely went more than a few weeks without seeing each other. Clara’s death in 1896 wrecked Brahms, preempting his own drastic health decline and eventual demise less than a year later.

Why did Brahms eventually break off his relationship with Clara if they were so deeply in love? What was holding him back from marrying this woman, clearly the love of his life? Was it the guilt he felt for loving a married woman and widow of his mentor, Robert Schumann? Or was Brahms simply unable to commit, choosing to adopt the relationship motto of his closest friend, violinist Josef Joachim: frei aber einsam (free but alone)? Or perhaps on an even deeper level, was Brahms unable to wed the private, sexual love he shared on his frequent visits with prostitutes with the deeply emotional and soul-bearing love he felt for Clara? Whatever the reasoning, Brahms saw past his prejudices and formed his only meaningful long-term connection with a woman.

With only one other person was Brahms (however briefly) able to look beyond his deeply embedded mistrust of women. On a visit to Göttingen in the spring of 1857, Brahms fell in love with the dark-haired, intelligent beauty Agathe von Siebold, a soprano who by all accounts had the voice of an angel. A little over a year later, after countless love letters back and forth, Brahms proposed, Agathe excitedly accepted, and they made it official with his and hers engagement rings. Word got out and the music community was abuzz with gossip about the impending wedding. But it was not to be.

Brahms left Göttingen to perform his Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 51 with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. The people of Leipzig, home to Felix Mendelssohn, had never been receptive to the music of Mendelssohn’s younger archrival—and this was no exception. Brahms, who performed as the soloist, reported the tragic details of the work’s reception to Joachim, writing, “at the end, three pairs of hands were brought together very slowly, upon which a perfectly distinct hissing from all sides forbade any such demonstration.” Brahms was similarly slammed by the critics. One wrote, “the ideas slip away either dully or sickly… only extremely seldom is there organic development and logical continuation.”

Feeling dejected and embarrassed, Brahms hastily broke off the engagement with Agathe. He wrote to her, “I love you! I must see you again! But bound, I cannot be!” As a composer who was already deeply insecure about his music and his place in history, Brahms couldn’t stomach displaying his inadequacies to someone he loved. Brahms was unable to look into his fiancée’s eyes after such a harrowing experience, admit failure, and accept her pity—and this, he claimed later in life, not his independence, was the real reason for the break. At the core of Brahms’ reasoning for the break was deep-seated insecurity that spanned many aspects of his life—from his music, to his humble beginnings, to his own manhood.

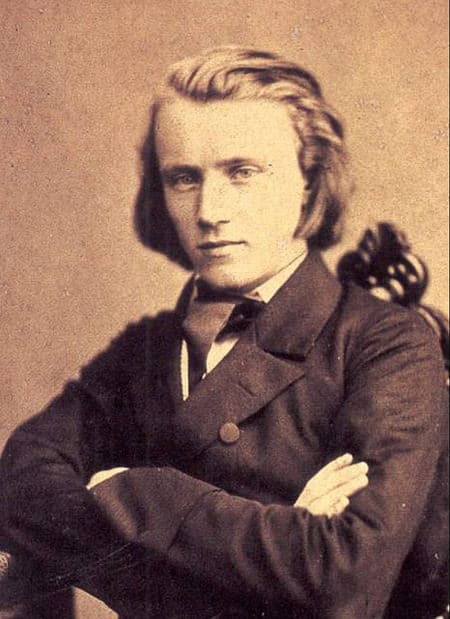

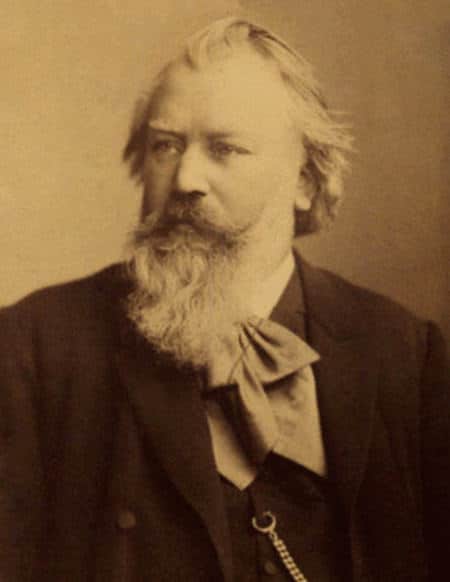

Brahms, from his teens, was deeply insecure about his physical appearance; and it’s no surprise for he was an extremely late bloomer. At the age of 20, Brahms could have easily been mistaken for a child. He was short, blonde, blue-eyed, and fair-skinned. Brahms’ friend Hedwig von Salomon described the 20-year-old as having “a thin boyish little voice that has not yet changed and a child’s countenance that any girl might kiss without blushing.” Brahms’ voice reportedly did not change until he was at least 24-years old, by which time it was already permanently damaged by Brahms unnaturally forcing it lower, presumably to sound more “manly.” His beard didn’t start to grow until his mid-30s. It wasn’t until 1878, at the ripe age of 45, that Brahms managed to grow the large, impressive beard often associated with him today.

Without a beard, Brahms felt diminished and out of fashion. He described it to his friend, J.V. Widmann, as being “long suppressed,” adding that without a beard he was often “taken for an actor or a priest.” Being so physically underdeveloped in a time when the archetypal 19th century German man appeared large, bearded, and virile, was excruciatingly difficult for the young Brahms. In this context, his lifelong choice, to limit his romantic sexual relationships to prostitutes—women who would not assess him on his manliness or artistic success, but rather, the size of his wallet—makes complete sense. And his hesitation to commit to a long-term romantic relationship, one that would expose his self-perceived physical and artistic weaknesses to a woman is understandable.

One can only imagine the horrors Brahms experienced in those Animierlokale at the hands and on the laps of countless prostitutes—how the abuse set upon him shaped his sexual preferences later in life. As a child, his innocence and weaknesses was put on display for the amusement of others. And it seems that, for the next 50 years, Brahms was simply trying to avoid having that happen ever again. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.