“I don’t know if there is a creator, but if he exists, all I could do is tip my hat to him and say, ‘Thank you,’” pianist and conductor Lars Vogt told me in May 2021, when we spoke shortly after his cancer diagnosis.

Vogt died on Monday in a hospital in Erlangen, Germany, surrounded by friends and family. It was three days before his 52nd birthday. He once said of the cellist Boris Pergamenschikow, “He was a genius at bringing people together who think in similar ways,” and the same thing applied to Vogt himself. Vogt brought people together in many places and on many levels: at his Spannungen festival in Heimbach, Germany, which became a musical home for a generation of musicians and listeners; for children with his Rhapsody in School project; with his two orchestras; and with audiences from the stage.

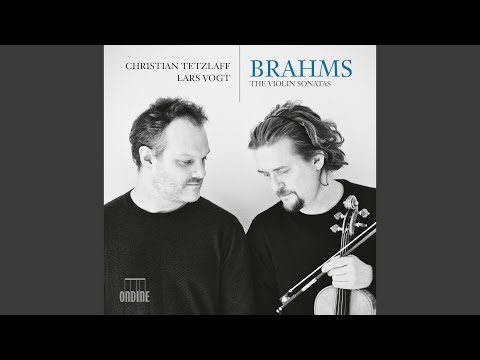

Four years ago, Vogt told me about the combination of a strong personality and lack of egotism he looks for in colleagues. Classical music has a way of promoting ambitious individualists, but Vogt raised a family of performers. “More than anyone else I know, he’ll have a legacy, not in terms of, ‘What a great career, these are the CDs he released,’ but a legacy in the real lives of other people whom he touched,” said violinist Christian Tetzlaff, one of Vogt’s closest friends and chamber music partners. (Their most recent album, “Beethoven: Sonatas Op. 30,” was released last year on Ondine.) I reached Tetzlaff the day after Vogt’s death from his home in Berlin.

VAN: How are you?

Christian Tetzlaff: As well as can be expected. There are waves of grief. We’d been talking on the phone every day, and I’ve realized that I’m still talking to him. Luckily I was with him in his final days and could say goodbye. His death was not a surprise. We knew it was coming. That made it easier for those of us who were close to him to process. It doesn’t lessen the grief, but does make the moment itself less shocking.

Still, did something change for you when he was suddenly gone?

Something strange just happened: I’ve been watching our three children by myself, I’ve been busy; but then I heard the news on the radio, and my eyes welled up, because it was official in a way—like it’s true. I’ll probably be in between worlds for a while.

Something that’s made it easier to handle is that we were with him in Erlangen for his last days, with many musician friends, with his whole family. We sat with him, played for him, talked to him—and up until the end he was the same person. He was still able to smile and laugh at the little things. He joked: “Imagine the doctors were wrong, and things won’t end badly, then I’ve just had a really great weekend.” Those are the things that make it possible to process.

The amazing thing is, I don’t know anyone who’s as beloved as Lars Vogt. Beloved by such different people from such different backgrounds. You can tell that the people he touched felt completely accepted by him. He combined so many things. He had this baroque personality; he enjoyed everything and had a wild life. He was at once the wildest and most sensitive musician I know. He had an unbelievable ability to connect. One person managed to connect such an unlikely group of musicians, while most people are off chasing their individualistic goals. He made us see ourselves as a big family, and that will go on. Loss is not the only thing we’re feeling.

Did you get to know him first as a musician or as a person?

As a musician. 26 years ago, we played a concert together—Heinrich Schiff connected us. Then he started the festival in Heimbach and it became very intense. He’s my best friend, my closest comrade. With musicians, I don’t differentiate between the music they play and who they are as people. I’ve met a lot of musicians who have become very successful by talking about themselves, presenting themselves well, and who seem to have no experience with doubt— and, going further back, with musical dictators, who were successful because they forced everyone to follow their will. But I learned that music can only speak fully in freedom and love.

It’s a thing you only experience with very few musicians, artists like Lars. We communicated about the darkest and most joyful things, and we experienced those same things in concert, without the protective layer, without the illusion of being invincible—we were totally vulnerable. For us as interpreters, I think, that’s the only approach that does justice to the composer. We’re not talking about ourselves; we must have enough empathy to follow Herr Brahms on his path.

And this was possible talking to Lars and performing with Lars, and I think that’s why he made sounds no one else could. He could play softer than anyone else, but also louder. When we were on stage, us strings could play fearlessly. He could sound like an orchestra, but in such a way that the person he wanted to hear in that moment was never in danger.

That is a human quality. It has nothing to do with saying, “Play softer here, I can’t hear my part.” Instead it was a constant adjusting to one another and not needing to be in the foreground. That’s a fundamental attitude for a musician to have, and it’s what makes his versions of the Brahms and Beethoven Piano Concertos different from any others I know.

His attitude towards a Brahms Piano Concerto is: We’re doing this together. There’s a solo cello playing here, an oboe here, a horn there, and each one is my friend. It’s a quality that you hear in the unbelievable performances with him conducting the Northern Sinfonia or the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris. They show that every musician has something important to say if you let them. Of course there’s a certain hierarchy, the conductor leads, but when it comes to the details he needs to trust his musicians, and if he does they all transcend themselves. That’s the true mark of a conductor’s quality. Bringing an orchestra together and saying, “My way is the right way” works too, but the results are completely different.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Is this trust the prerequisite for allowing musical differences to shine?

Right, that makes it possible. When one person is convinced of something, then we should immediately try our best to understand it. But when there actually are different approaches to the piece, each with solid justifications behind them, then you can do things differently, instead of arguing. You’re saying, “I think the way you do it is great, but I’d rather do it this way, and we’ll get them both on the same level.” It’s not a compromise. It’s about valuing what the other person has to offer.

You described Vogt’s personality as “baroque.” He once said that you are the most “thoughtful person” he knew. Is that a difference between you two that bore fruit in your music-making?

It’s easy to see a contrast there, between understanding something and expressing it passionately, but in the best case the one makes the other possible. When you get to the essence of a composition by trying to understand its motivations, you actually arrive at wilder or more profound results. Maybe we started from a place of being very different, but in the last 26 years we usually found each other or even overlapped.

Vogt once said that the professional pinnacles didn’t always coincide with the happiest musical moments: “There were times when I played with Christian and Tanja [Tetzlaff] somewhere in a tiny chamber music venue, and we were so happy.”

That’s usually true. The best moments, where you think, “Wow, it was right today, everyone was moving in the same direction,” often happen by chance. Maybe in a small hall somewhere, probably more often in Heimbach, because of the atmosphere. The “professional pinnacles” are usually more fiction than fact.

Off the top of your head, what are some especially memorable performances that you played together?

The final concert in Heimbach a few weeks ago. We played Brahms’s great Piano Quartet in C Minor, which deals with the theme of death. Lars had COVID and two weeks of heavy chemotherapy behind him, and he played like a god. In the back of our minds, we thought that was probably the last time we’d play the piece together. And then, two weeks ago, we played the Brahms G Major Sonata in the hospital with an electric piano. Both were unbelievably special. I mention these two performances because on his last day, on the day he died, he said, “I can hear music in my head right now, a ballade, by Brahms I think.”

For both of us, Brahms felt so close. He was there in moments of deep emotion. Maybe because he doesn’t seem as superhuman as some other composers, or as addicted to desperation, but instead—to quote his requiem—says, “I will console you, as one is consoled by a mother.” It’s something that resonates even in the darker Brahms works. He isn’t trying to be bigger than us; he wants to be with us. Brahms is the composer who connected Lars and I the most all these years and who allowed us to say goodbye in such a beautiful way.

You continued to perform with Vogt throughout last year. Did you have to try and ignore his diagnosis?

No, it was a part of all our conversations, and it was in every note we played. We recorded the Schubert Trios the day before he went in to be diagnosed, because we knew that something was very wrong. The way he looked and felt showed that there was a real threat. That was a year and a half ago. Since then we knew that our time was limited. It was always there, in the beauty and pleasure of the thing as well. Music suspends time. You’re in a different space. If anything is true, then this: Our music-making was especially intense this past year.

Is there a piece that you associate especially with him?

Yes, the Brahms Sonata in G Major.

Can you imagine playing it with another pianist?

I don’t know, but probably not for now. There are a few pieces that have question marks next to them, because of the way life goes. But who knows, maybe in a few years, with happy memories of him.

Four years ago, Vogt told me that he’d spoken about the moment of death with you. What was it like at the end?

At the end he wasn’t asking any philosophical questions, but there was such a surfeit of love from us all, standing by him, touching him. For me at least, that renders any further questions about the meaning of life or whatever comes after unnecessary. For me, we’re here to spread goodness and love as much as we can, so that it’s beautiful to be here, so that we can take pleasure in this unbelievable opportunity to be on earth and perceive beauty. Love is the key to that. He was surrounded by love, which he reflected up until the very last minute. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.