The American composer George Crumb lives in an unassuming two-story house, tucked away on an acre plot of land in Media, Pennsylvania, a sleepy suburb of Philadelphia. Recently, he met me at the local train station in his old maroon Toyota, and after a short drive along winding back roads, we arrived at his longtime home. As we pulled into the driveway, a small woman, who I would soon find out to be the spirited Liz Crumb, George’s wife of 67 years, appeared in the doorway. “George, pick up the paper!” she shouted. “Oh, alright” replied the 87-year-old composer in his endlessly endearing, slow, southern drawl.

In a determined and carefully choreographed sequence of movements, Crumb used his cane, the car door, and steering wheel to gingerly lift himself out of the driver’s seat. As he explained to me on the drive from the train station, his hips were not what they used to be. They were stiff and painful, making it difficult for him to get around—a constant reminder of his many years on this Earth.

I was greeted at the door by two strong, big-boned muts named Zeus and Smarty Pants, who had an apparent affection for strangers. Mrs. Crumb proudly recounted how her daughter Ann, an award-winning singer, actress, and part-time animal advocate, founded “The Rescue Express,” an adoption website that brought these dogs (who were scheduled to be euthanized) to the elderly Crumb’s household. These dogs escaped death, Liz said, and somehow ended up here, in “heaven.”

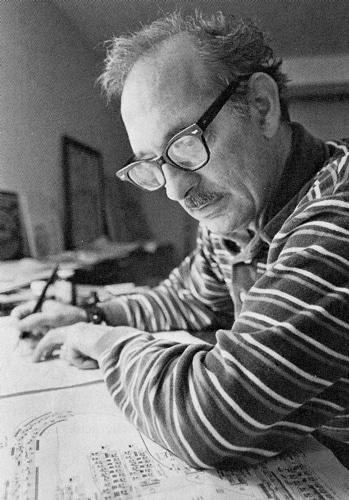

After a quick tour of the modest and well-worn interior of the house, we moved on to George’s study. It was crammed full of letters, medals, programs, awards, manuscripts, sketches, photo albums, and a few giant leather-bound scrapbooks (six of these, Crumb later told me, were recently gifted to the Library of Congress). In a room full of some of the highest accolades in the world of music composition, all unceremoniously placed around the room, I was immediately reminded of Crumb’s humble upbringing.

George Henry Crumb, Jr. was born and raised in Charleston, West Virginia, which he calls “the heart of Appalachia.” His father George Sr., a clarinetist, and his mother Vivian, a cellist, were members of local chamber groups and the community orchestra. Crumb began lessons with his father at the age of seven, starting on the smaller piccolo Eb clarinet, as his fingers were not yet big enough to reach the holes of the standard-sized Bb clarinet. Crumb played duets with his brother and father, and later, as a pianist, Beethoven and Brahms clarinet trios with both parents.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

After graduating high school in 1947, Crumb enrolled as a composition major at Mason College, a conservatory in Charleston. There he met a beautiful straight-shooting piano student named Elizabeth May Brown. The two were married shortly thereafter. To earn extra money on the side in his college days, Crumb worked as a pianist for a local ballet studio and as a self-styled organist and choir director for a small Baptist church. He later described his organ playing (especially his pedal technique) as “atrocious.”

This hodge-podge of early musical experiences played an enormous role in shaping Crumb’s mature compositional sound world. Central to Crumb’s artistic vision is the belief that what a composer hears throughout life has a profound impact on his or her sonic sensibilities. “I think composers are everything the’ve ever experienced, everything they’ve ever read, all the music they’ve ever heard. All these things come together in odd combinations in their psyche, where they choose and make forms from all their memories and their imaginings,” he told an interviewer in 1988. In addition to the more academically “sanctioned” Protestant organ music he played at church, the ballets he played for the local dance company, and classical repertoire he played at home, Crumb internalized the earthy sounds of Appalachian folk music. “I suppose, like all Americans at that time or any time, I heard the pop music of the day and a lot of folk music, which is rather strong in Appalachia. These were sounds in the air.”

After George earned his Master’s degree in music composition at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, the three piece Crumb family (Ann was now a toddler) moved to Ann Arbor, where he pursued doctoral studies in composition at the University of Michigan. As a student, Crumb exhibited a fascination with musics outside the Western tradition—something that would later become a hallmark of his musical thinking. In an 2011 interview with David Starobin, Crumb describes hearing non-Western music recordings for the first time: “I heard in the [Smithsonian] Folkways Series, music from Africa, the Orient, South America, and I never forgot these sounds. They seemed so beautiful in their own right. I thought maybe they could be used in Western music.” After a couple short-lived teaching stints in Virginia and Colorado, Crumb successfully acquired a tenure track position at University of Pennsylvania in 1965, where he would stay for the remainder of his teaching career.

It was over these transitional years that Crumb began heavily incorporating recognizably non-traditional instruments and sounds into his music. With his first mature work, “Five Pieces for Piano,” Crumb integrated conventionally produced piano sounds with special inside-the piano-timbral effects to create subtle allusions to the banjo, dulcimer, and bottleneck guitar, instruments common to West Virginian folk music. From here on out, Crumb would look to regularly employ instruments and timbres not just from Appalachia, but from around the world, using instruments like Tibetan tuned prayer stones or the African Udu.

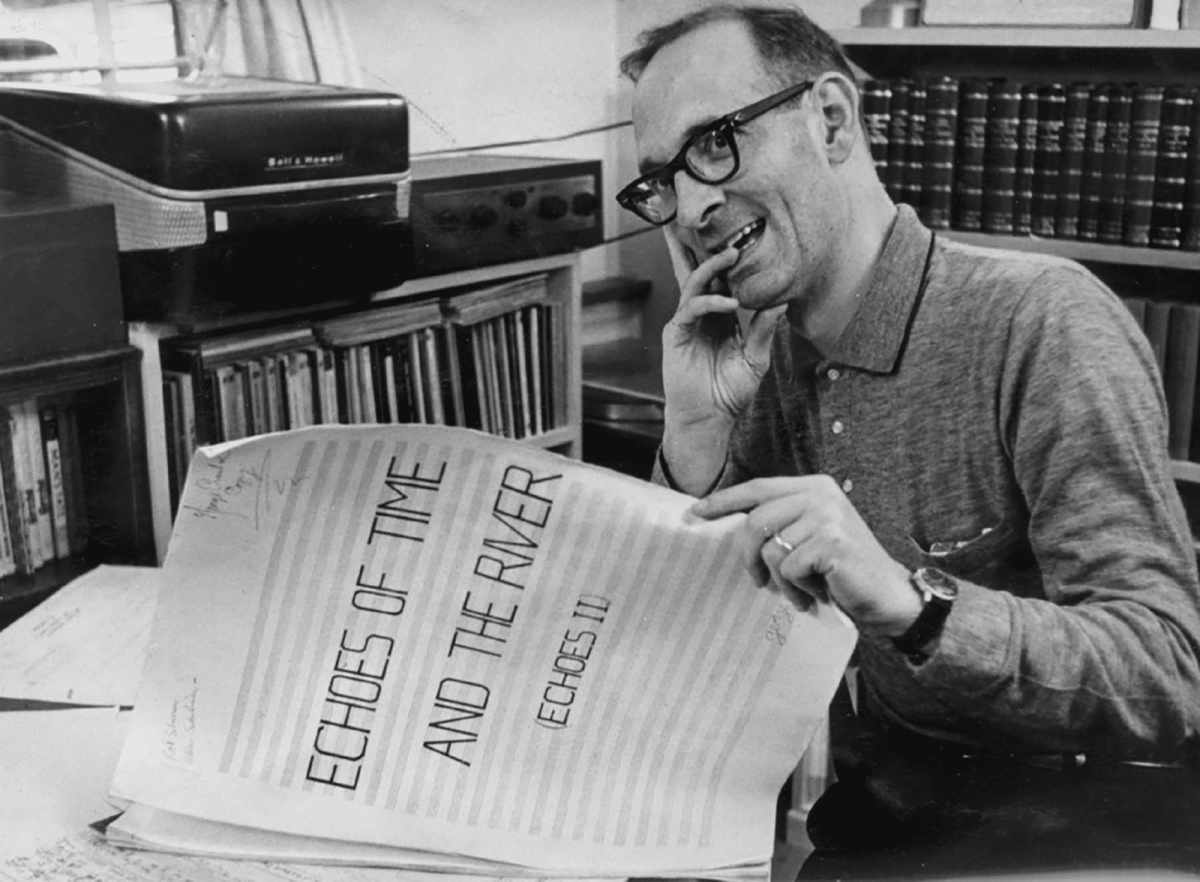

In the mid 1970s Crumb achieved major success with his “Black Angels,” “Ancient Voices of Children,” and “Vox Balanae.” His sweeping popularity waned a decade or so after these landmark works; nonetheless, he secured himself a place in history, often being cited in today’s Western music surveys, anthologies, and textbooks for his contributions to the field. In the new music community, he is still frequently fetishized for the innovations of his works, such as his radical approaches to notation, like using spiral or cross layouts, or his use of extended instrumental techniques, like singing and playing into a flute, dipping a gong into water, or tuning the unison strings of the mandolin a quarter-tone apart. More importantly, I’d argue, is his ability to bring new audiences to the often impenetrable avant-garde of the time. Lacking the characteristically repetitive and consonant gestures of the minimalists, who were also gaining popular success in those days, Crumb’s music nonetheless managed to take hold among average audiences: something truly remarkable for a rigorous art music of the post-war decades. In a 1986 retrospective of the composer, Suzanne Mac Lean writes, “[Crumb’s] music touches emotional depths in his listeners, and leaves them with the feeling that serious music, which for so long seemingly abandoned them, is once again succeeding in communication.”

Today, some 40 years after reaching the peak of his widespread acclaim, Crumb continues to compose, albeit at a significantly slower pace. Crumb’s views on music and the world have stayed notably consistent. And it is this characteristic consistency in his worldview and compositional practice that has sustained his music and its impressive communicative power.

Essential to this worldview is Crumb’s vision of a progressively unified culture. He envisions a more singular musical world where previous boundaries disappear, as music is exported from far flung places with ease brought by the information age. In 1980 Crumb wrote, as part of his forward-looking article “Music: Does It Have a Future?” that “the total musical culture of Planet Earth is ‘coming together,’ as it were. An American or European composer, for example, now has access to the music of various Asian, African, and South American cultures. …This awareness of music in its largest sense—as a worldwide phenomenon—will inevitably have enormous consequences for the music of the future.”

Speaking with Crumb at his home, I found that not much has changed in his worldview since the 80s. “You know, that’s the principle I’ve stuck with always. I think music is everything and anything you want to use including borrowing from Asia, North Africa, South America,” he said. On the one hand, Crumb’s consistent calls for a “unified music,” one that synthesizes and freely borrows sounds from other cultures, coopting them for use in Western classical music seems troublingly naïve, never calling into question the ethics of such borrowing and therefore avoiding a confrontation with the inherent power dynamics at work in Western music’s history of sonic appropriation. On the other hand, his childlike fascination with the sounds themselves and his continual search for renewal in Western music seems nothing but honest and good-willed. Wherever one stands on the ethics of appropriation, it’s undeniable that Crumb, by incorporating in his work sounds from other cultures, succeeded in finding a timbrally rich sound world unlike any of his contemporaries.

For much of the last decade, Crumb has been working on a monumental cycle called the “Seven American Songbooks.” All together, these contain 65 individual movements, 62 texts, and more than 150 percussion instruments, totaling over five hours of music. One of the most poignant cycles is the second, titled “A Journey Beyond Time: Songs of Despair and Hope, A Cycle of Afro-American Spirituals.” Crumb sets melodies and text from the tortured past of Blacks in America in “Steal Away”:

Steal away, steal away,Steal away to Jesus;Steal away, oh, steal away home;I ain’t got long to stay here.

To accompany this spiritual—a perhaps coded call to flee slavery on the Underground Railroad—he creates a haunting atmosphere of metallic sounds using percussion originating from East Asia (Chinese Cymbals and Temple Gong), India (Indian Camel Bells and Ankle Bells), the Caribbean (Steel Drum), and the more traditional Western classical percussion battery (tubular bells, cymbals, wind chimes, tam-tam and struck and bowed vibraphones).

Trying to pin down from where his impulse to borrow came, Crumb referenced the long tradition of collage in Western music. “You know Bartók combines all systems in his music. I don’t think he ever wrote a 12-tone piece. But he’s written so many pieces so excessively chromatic that it makes Schoenberg look like a faker, in terms of sheer raw dissonance. And then he’ll just have major chords in one,” he told me. Spinning his chair around to the grand piano which sits nestled in the corner of his study, he continued, “The Violin Concerto, you remember”—he played Bartok’s Violin Concerto No. 2, second movement while singing the main melody in his creaky baritone voice, and laughed—“good ol’ B Major!”

When it comes to borrowing from European masters, Crumb has some clear influences: Mahler for his orchestrations and use of non-traditional sounds, from Alpine cowbells in the Symphony No. 6, to the mandolin in the Symphony No. 7; Debussy for his use of Gamelan-inspired timbres and repetitive rhythmic cycles; and Beethoven for, among many things, his timbral invention. “I moved into the position of considering timbre as important as rhythm, harmony, and counterpoint. Beethoven was onto that already. He used con sordino more than any of his contemporaries…you get this magical sound,” he said.

Crumb, “Night of the Four Moons”; Valeria Martinelli (Mezzo soprano), Haydée Schvartz (Conductor), Ensamble TROPI

Crumb’s admiration of the music of the past also appears through his frequent use of tonal quotations. A subtle pentatonic fragment in his “Night of the Four Moons” recalls the last movement of Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde.” “Dream Images (Love-Death Music) Gemini,” from the piano cycle “Makrokosmos” (a title which is itself a reference to Bartók’s cycle “Mikrokosmos”) features a substantial note-for-note quotation of Chopin’s Fantasy Impromptu. This opens his music to the possibility of rich, multifaceted interpretations. In Crumb’s search for new sounds, he looked to the past, recontextualizing these familiar melodies.

Crumb’s works create the effect of a certain timeless relatability. Their quotations and references are an essential part of this. The musicologist Richard Taruskin marvels, “the ingredients in Crumb’s collages were chosen not as representatives of styles but as expressive symbols of timeless content.” In contrast to other modernist composers of the day, who would not dare make tonal allusions in their music, let alone quote an entire passage of Chopin, Taruskin writes, “Crumb’s [compositions] seemed virtually amnesiac, drawing on the music of all times and places as if it were all part of one undifferentiated ‘now.’ ”

Yet communication with an audience has never been a central concern of Crumb’s. When asked about the role of the composer today in America he paused for a moment. “I never thought about it actually. His or her role would be to write music—to express thoughts through music and hope people can react to it in a way that makes it all worthwhile.” When I pressed him on whether or not he strives in his music to communicate with audiences, he replied, “I am, but I’m not overwhelmed with that. I’m more worried about bringing out what I want to say, and hoping that once it’s there, that it does communicate. But I think you write for your own ears and hope that because it satisfies you, it might attract someone else.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine, and we’re able to do so in part thanks to our subscribers. For less than $0.11 a day, you can join our community of supporters, access over 500 articles in our archives, and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

(PS: Not ready to commit to a full year? You can test-drive VAN for a month for the price of a coffee.)

Comments are closed.